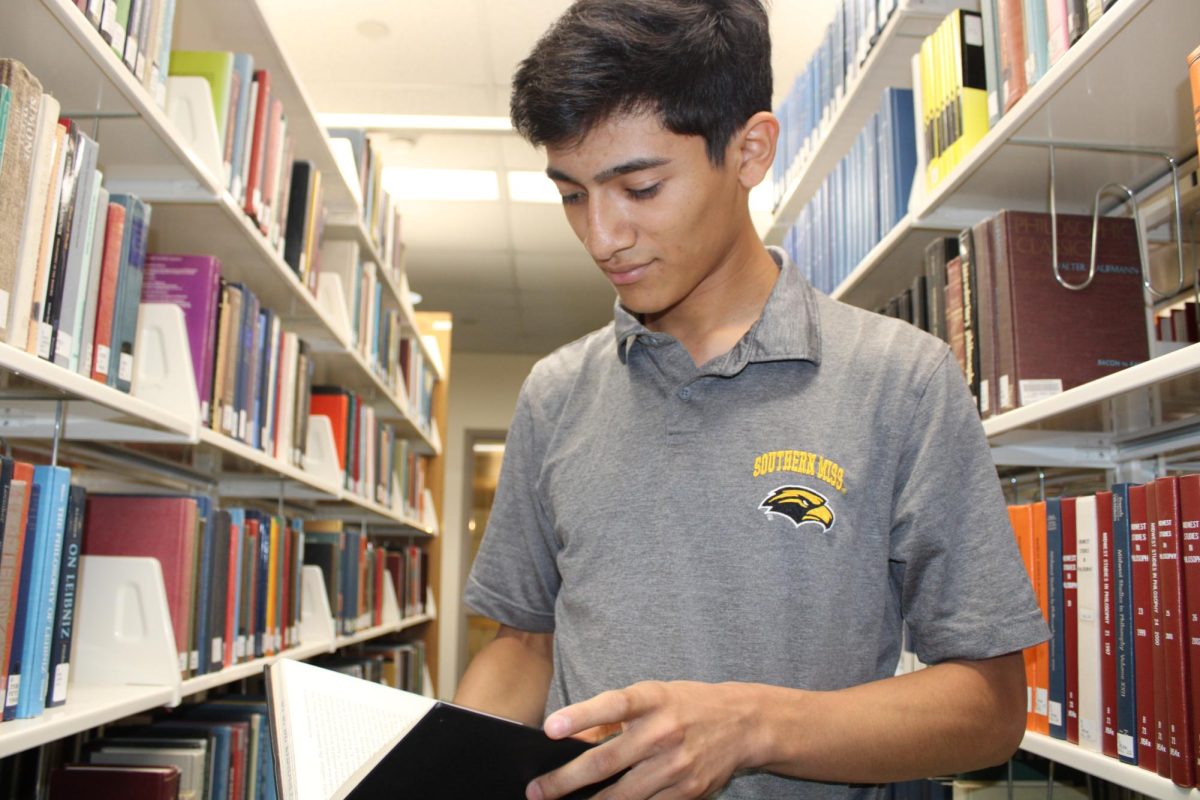

A research project, led by sophomore philosophy major Maya Rex and professor- adviser Elena Stepanova, seeks to investigate the effects of skin color and facial features on racial bias in elementary school children.

USM researchers hope to potential curb prejudice by learning when and why these behaviors arise during the course of an individual’s psychological development.

Currently in the data collection phase of their project, Rex and Stepanova have surveyed 100 children so far from Dixie Elementary, North Forrest Elementary and both the Hattiesburg and Petal branches of the YMCA and hope to collect from about 20 more.

Stepanova has spent many years studying social and personality psychology. The Psychology Department study reflects Stepanova’s doctoral dissertation, which focused on the visual cues of skin tone and facial features and how they affect racial categorization. Stepanova said researchers have postulated categorization is a critical first step in the development of prejudice.

“Essentially we group people into different categories, and we look at certain visual markers the help us to do that,” Stepanova said. “We do have preconceived ideas, stereotypes and feelings. [Once] we put a person into this group all these ideas associated get activated, so it’s important to study social categorization because it’s a precursor for prejudice, stereotyping and potentially discriminatory behavior.”

Stepanova’s previous studies found that adults tend to place somewhat equal weight on skin tone and facial features when placing individuals into racial categories.

The current study in progress seeks to measure the same behaviors in children between 5 and 12 years old. Stepanova, Rex and their colleagues hope to put these tendencies into a developmental context to better understand when and why these behaviors arise.

“I feel like children kind of reflect the views of society because they kind of absorb everything that people are telling them,” Rex said. “Adults have already had so much time to formulate their own opinions. Children are just little sponges soaking up what their family says, what they see on TV, all these other things.” Specifically, the researchers are interested in quantifying both the explicit and implicit attitudes of children toward different racial categories.

In the field of social psychology, explicit attitudes are understood as those ideas and feelings that individuals most easily identify and express.

“These are things you would consciously endorse and be willing to express,” Stepanova said.

Conversely, implicit attitudes are those ideas that are more difficult to recognize.

“These are the attitudes that people might not be aware of or be willing to express, the ones that are sort of pushed back that might not be accessible to us,” Stepanova said.

In order to measure these attitudes towards race in children, Stepanova, Rex and their partners have employed a software used in Stepanova’s previous research that produces computer generated faces of varying skin tones and facial features.

The task is framed as a computer game. Subjects are shown a series of faces and asked to rate how “good” or “bad” they think the face is on a sliding scale with a smiley face ononeendandasadfaceon the other. Stepanova published studies using this methodology last year that indicated that the explicit attitudes of younger children mostly rely on skin tone alone, while older children, starting around age 8 or 9, begin recognizing facial features as well.

The current study incorporates the same methodology to continue to measure explicit attitudes, but the researchers have added a second task in order to measure implicit attitudes as well.

The program shows children a series of random Chinese characters and asks them to indicate whether they believe the character means something good or bad. The key to this task is that for a brief moment, maybe half a second, a computer generated face flashes on screen before the character. Subjects responses regarding the character are then correlated with the skin tone and facial features of the preceding face.

Stepanova said their sample is exciting one due to the demographics of the area participants.

“Here we got lucky because we have a great diversity in our local [schools], so about half of our participants are black and half are white children,” Stepanova said. “What I am especially interested in is to compare the responses of white kids versus black kids and whether or not there is discrepancy in their responses in these tasks.”

Rex, who was awarded a SPUR grant for this project, said her experience in this research has inspired her to pursue a career in social justice law.

“This has shown me that the hope is in our children knowing things and understand things and wanting things to change,” Rex said. “I feel like our generation is one of the first to see things for what they are, and if I want to help people, I need to do something. Law is a big way to do that, especially being a woman and being black. I feel like there’s not many people that look like [me] in the law scene and I feel like I should be there.”