Kate Dearman/Printz

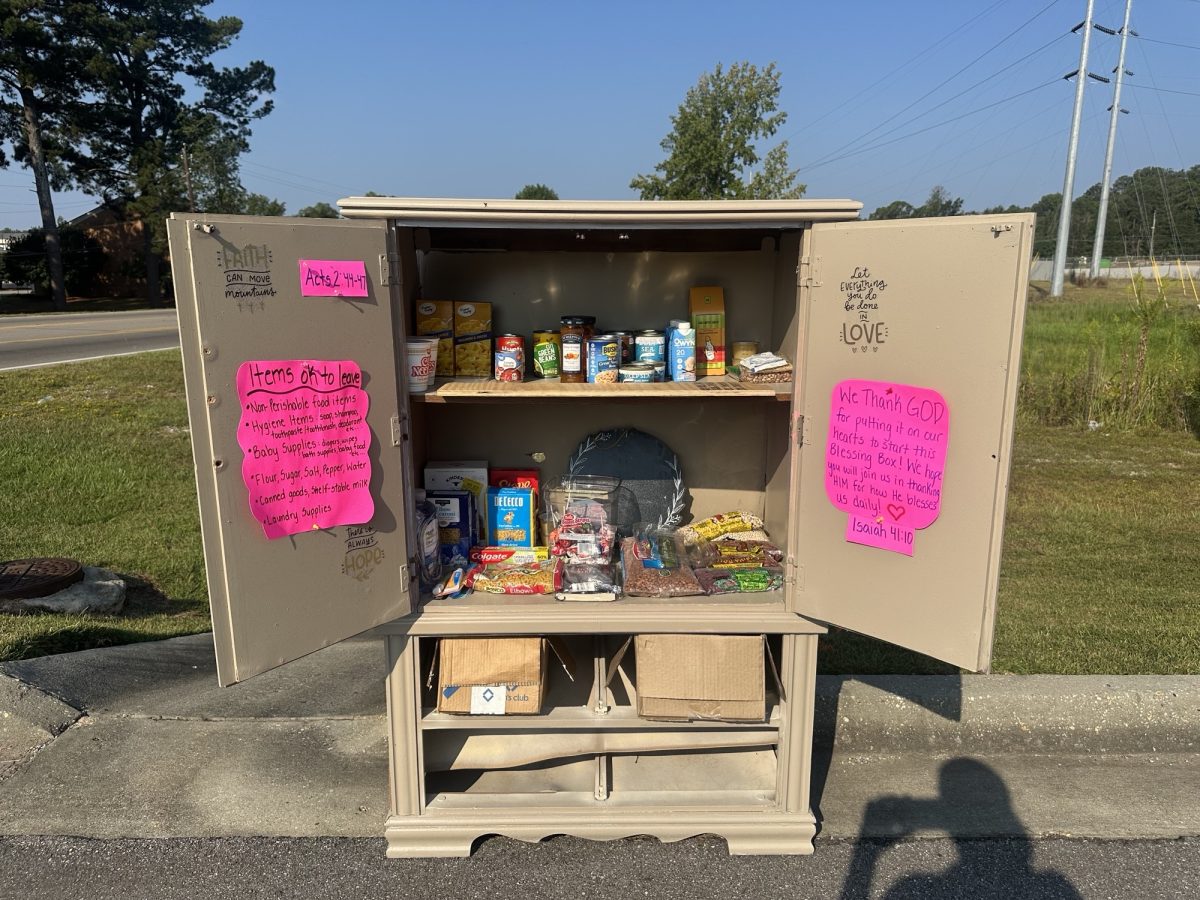

“Twelve clubs, a physician, a pharmacy, a taxi service, a dentist, cleaners, houses for all your eyes could see,” said Eddie Holloway, USM Dean of Students. He also served as city council president for 12 years. “It was a mecca of business, like Memphis’ Beale Street and Atlanta’s Auburn Street.”

In 2014, one can see Mobile Street is not in quite the shape it was a half-century ago, when African-Americans were fighting for their right to vote.

Jan. 22, 2014 commemorated 50 years since the 1964 Freedom March, starting on the corner of Seventh and Mobile Street and continuing to the Forrest County Courthouse on Main Street.

Peggy Connor, who served as executive secretary of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1965, owned a beauty salon on Mobile Street during the time of the march.

“It started at the Copher office,” Connor said. “It was a three story building, now a vacant lot. Kids stayed out of school that day, and 50 ministers came from the North to lead us up the street.”

The Rev. John Cameron was in his thirties in 1964, when the Freedom March made its debut in his hometown of Hattiesburg.

“We would march about the Confederate statue (located to the right of the building), 41 at a time,” Cameron said, remembering the events of the first Freedom March.

“They’d arrest 41 of us, and another 41 would come to take our place. Eventually, we’d filled all three of the jails. We stayed there for three days, three nights until bail from (church organizations) were sent to release us.”

Cameron said the case was taken to court for the charges against them were unlawful. They lost their case to the state of Mississippi justice system, but when taken to Supreme Court, they won.

Anthony Harris, son of activist Daisy Harris, spoke outside the Forrest County Courthouse on his arrest 50 years ago as an 11-year-old boy.

Mississippi passed a law banning individuals under the age of 18 from the picket line against First Amendment rights.

Harris, his older brother and a friend were arrested and menaced by police officers until Daisy arrived, demanding their release.

The officers threatened the boys with a BlackJack.

It was about that time Daisy Harris burst into the police station and demanded their release.

Kate Dearman/Printz

“My mother put her own safety, her own security and own freedom as secondary and stood up for the right thing,” Harris said. “In the end, good triumphs evil.”

“It was scary sometimes back then,” said Leonard Marris, lifetime resident of Downtown Hattiesburg who was a student at Eureka in 1964. “Changes have certainly happened since I was in school.”

Eureka was the first and only African-American school at the time, built in 1921.

Connor reflects on said changes, but still has a heavy heart for the Hattiesburg community.

“There’ve been many changes, but the laws made the change,” Connor said. “Real community change comes from the heart. You can see our past arise in events like the (2013 Hattiesburg mayoral) election.”

And the rigid divide is as literal as it is historical.

“All African-Americans lived east of the railroad tracks,” said Holloway, gazing upon the now vacant lots and the many decrepit buildings lining Mobile Street.

In 2014, one may see the demographical distinction between West Hattiesburg, being nearly 75 percent white and East Hattiesburg holding a 50 percent black population.

Glenda Funchess, who runs the Civil Rights Institute for Young Children, was around 10 years old in 1964 and attended Freedom School at Mt. Zion in Hattiesburg.

Donning a bright yellow NAACP sign stating “PROTECT VOTING RIGHTS,” Funchess carries on the tradition of marching.

“I attended the March on Washington in August, and we also are very active participants in Atlanta,” Funchess said. “If there’s a march, we’re usually there.”

Funchess remembers the 1964 Mississippi and poignantly remarks on today’s Mississippi.

“We made some steps towards equality, but now I believe we’re regressing,” Funchess said. “Hattiesburg had a horrible voting history (and) 500 African Americans lived here, but only about 50 were on the roll.”

Funchess equates the 2013 Voter ID movements act as a modern poll tax and disenfranchises African-American’s right to vote.

“I think it’s going to be very hard to (move on) until people lose the attitude of superiority. It’s not about skin color; it’s about content of character,” Funchess said.

Mississippi, notoriously a Republican state today, was Democratic at the time that Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act.

“It was then we saw a shift to the Republican Party,” Funchess said. Democrats existed throughout the state, but African-Americans were barred from representation, thus the emergence of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP).

Connor co-founded the MFDP along with activists Victoria Jackson and J.C. Fairley and attended the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, N.J. She had close ties to the struggle in Hattiesburg particularly.

“You know, they thought we’d stop (protesting) after this day 50 years ago, but we kept pressing on everyday thereafter for months,” Connor said.

Connor was arrested for picketing in April 1964 outside the Forrest County Courthouse, where about 150 marched today.

“We will be celebrating all year,” said Victor Booth, a lifelong resident of Hattiesburg, as marchers sang the traditional song, “We Shall Overcome.”

“The great experience is the freedom to speak on these topics,” Booth said. “In ’64, we didn’t have that. Now we can speak and speak about what’s against us. We have the knowledge and the right. In the end, we’re all God’s people. That’s how it should be.”

Looking down the street he has lived on his entire life, Holloway reflected once more on its people and its history. “Everyone knew everyone, and we went through a lot together. I don’t find peace with moving.”

The Freedom Summer dialogue series, sponsored by USM Center for Black Studies, will continue February through May to recognize and commemorate the participants of the Civil Rights Movement.