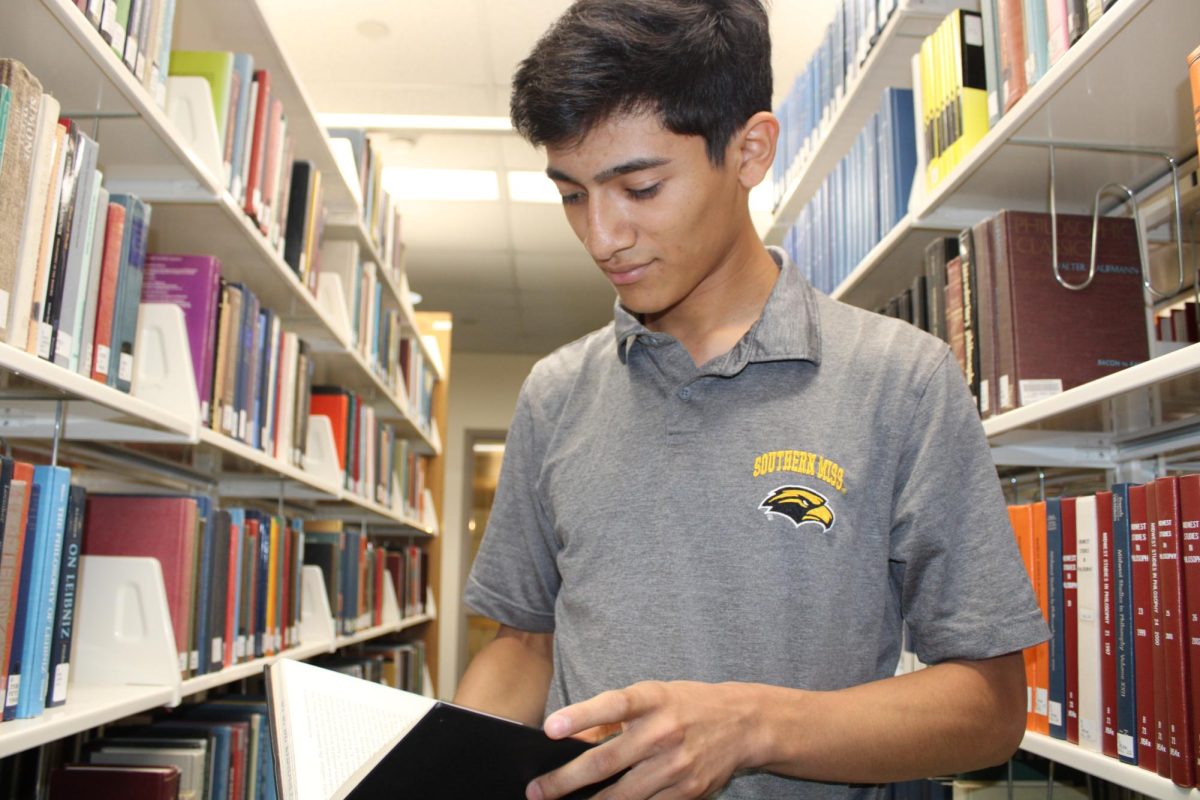

Associate professor Cheryl Jenkins, Ph.D., has heard she is someone’s first black professor annually since she started teaching at Southern Miss in 2008.

Now the comment isn’t as surprising as it was the first time she heard it. As one of the few black full-time professors, Jenkins said she is drained by the pressure to provide an experience for the black students in her journalism and black studies classes.

“It’s very intimidating because I don’t know what it is,” she said. “I don’t know if they’re just looking for a black face or they’re looking for a black experience or if they’re looking for a nurturer. I don’t know what it means when you say you take a class because you want to have a black professor. I’m a human being, so I’m probably not going to give you whatever that thing is you’re looking for outside of just that

After two black professors in the School of Communication left in May, Jenkins is the only black professor left in the school.

According to the latest data from Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning, full-time black professors made up 19 out of 555 of full-time professors in Fall 2017. These numbers, which exclude instructors and lecturers, have remained nearly the same for the last 10 years. While university administration attempts to attract more minority faculty members, a national problem, some black undergraduates continue to look for black mentors on campus and work toward being the representation they aren’t seeing by pursuing graduate degrees.

“I’m disappointed by it,” Jenkins said. “Evidently, because I’ve heard [I’m someone’s first black professor] for 11 years, evidently it’s something that is necessary for students.”

Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Steven Moser said Southern Miss alters between meeting national averages for minority faculty to “dipping below slightly,” and the university could create better strategies to recruit and retain minority faculty. He said he has met with faculty groups to discuss minority faculty retention and has heard student concerns through Executive Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Amy Miller.

“I am encouraged by steps many units have taken to diversify their candidate pools in their faculty searches, and I am also encouraged that as an institution we are attracting more minority faculty applicants to disciplines that have traditionally been less diverse,” Moser said.

Moser said hiring has been more intentional through advertising in publications like The Chronicle of Higher Education, Inside Higher Education and Higher Ed Jobs, investing in supplemental search components that match minority faculty with open positions and using funds to connect early career faculty members and graduate students to Southern Miss through lectures and presentations.

Southern Miss’ Affirmative Action and Equal Employment Opportunity Office reported that minority representation is the highest in service maintenance workers, who made up 64% of that category in 2016. More specifically, students are more likely to see black service maintenance workers, who accounted for 113 of 226 of full-time service workers in fall 2016, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Senior psychology major Shundrell McMullan said she is used to seeing more nonblack faculty and students after attending predominantly white schools before coming to Southern Miss. Although she’s comfortable with talking to them, she feels she can’t relate to them unless it’s on an academic level.

Black students are second to white students as the highest racial group at Southern Miss. According to the Office of Institutional Research, black students were 29% of the student population in the 2018-19 academic year.

McMullan said nonblack students don’t try to understand black students’ perspectives, even in classes centered around race. When she took Multicultural Counseling, she thought to herself, “For a subject that deals with so many diverse cultures, where is this representation?” In the same class, she watched a black student call black women lazy as some nonblack students smiled. She was disgusted.

McMullan has taken classes taught by two black instructors, one of them a graduate student and the other a faculty member. She said she began thinking about the lack of faculty diversity when she took Sherita Johnson’s, Ph.D., Introduction to Black Studies course in Fall 2018.

“Our school promotes diversity, which I love, but I only see that within the student body,” McMullan said. “If black students are 29% of the population, then we need that same energy in full-time black faculty,” McMullan said. “I truly believe that our success can be altered by something as small as seeing black professors. As thankful as I am for him, having a black president is just not enough. It means more. It helps us realize that we can make it.”

University leaders create an affirmative action plan annually to comply with federal law. The plan focuses on equal employment opportunities for minorities, women, veterans and people with disabilities, according to Associate Vice President for Human Resources and Equal Employment Opportunity Director Krystyna Varnado.

Varnado said the current goal for minority faculty is 19.2%. Her office’s recent analysis found no underutilization, meaning the current percentage of minority faculty at Southern Miss was not statistically significant from the national labor market at 17.2%. The analysis does not break down faculty by academic rank or race and ethnicity.

“To achieve even greater diversity than the AAP requires, we have to be uniquely creative in recruiting those faculty members,” Varnado said.

Jenkins said black faculty members are most likely to look for jobs in specialized electronic mailing lists, Facebook groups and organizations dedicated to black faculty.

“That is where I’m going to go to search because it’s been vetted by someone who looks like me, who says this place is safe, and it won’t be so isolated,” Jenkins said. “If you want good quality black faculty, you go to their places.”

The McNair Scholars program aims to provide underrepresented groups, such as racial minorities and low-income and first-generation students, with research opportunities, mentorship and graduate school preparation.

Southern Miss alumna and former McNair scholar Tiara Watson graduated with a degree in psychology in May 2019 and is currently pursuing a doctorate in counseling psychology at Southern Illinois University.

Watson said despite Southern Miss being a predominantly white institution, university leaders do a good job of creating programs and organizations for minority groups. She also said the McNair program’s acknowledgement of the challenges minorities face to go into higher education inspired her to apply, and the networking and mentoring the program provides is vital.

“The goal of the McNair program is not only to motivate those underrepresented populations to go into graduate study, but specifically go into graduate study to obtain a degree to go back and teach at universities,” Watson said. “When you hear other people, see other people who look like you and hear their stories and aspirations it inspires you to keep going and contribute back to society and academia.”

“I feel like the whole infrastructure of society in education has to change … [The lack of black faculty] on college campuses is definitely not a surface level problem.”

In fall 2016, the national average percentage of full-time black professors was 5%, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

When Jenkins was pursuing her undergraduate degree at Southern Miss in the 90s, she wasn’t taught by any black full-time professors. When she was a junior, a black graduate student taught one of her journalism classes and inspired her.

“He wasn’t here long enough to mentor me, but the first opportunity I got to work with the Printz, the first time I was given reassurance in a class—like, ‘You got this. Good job,’—my first conference, everything like that that that prepared professional development I did was with him,” she said. “I had white professors who were mentors, but that instructor made me feel like I could actually do this.”