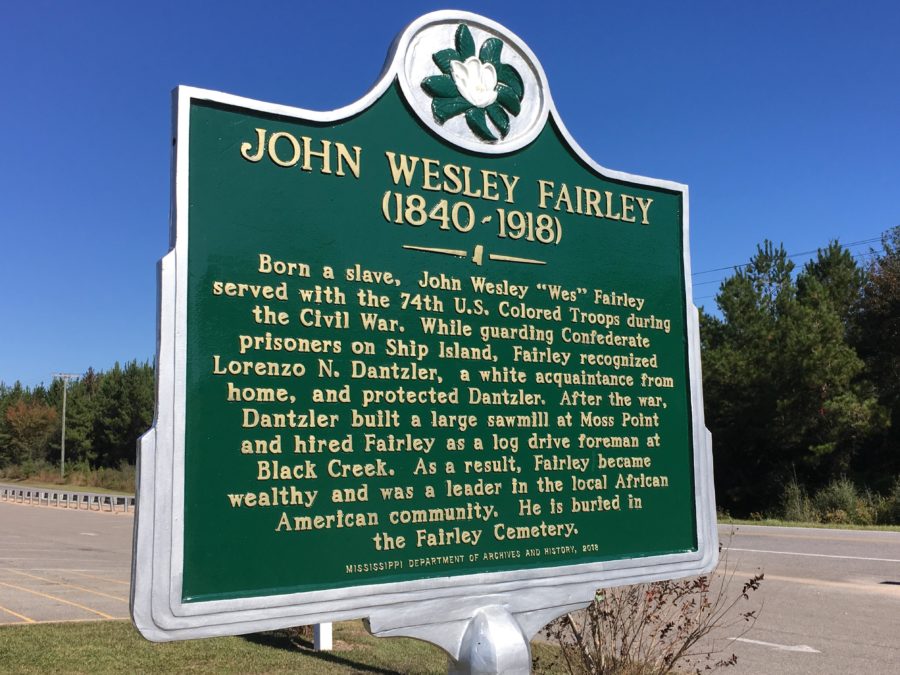

Hattiesburg has a long history involving civil rights, from The Freedom Summer, Kennard Washington’s denial of enrollment, Raylawni Branch and Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong’s acceptance to Southern Miss and even Vernon Dahmer’s story of voter suppression. Before these stories, there was a man named John Wesley “Wes” Fairley.

Fairley is not a civil rights hero, but he has a memorial in downtown all the same. Some have probably walked past his memorial a dozen times without noticing. Four bronze cast footprints approximately 14 inches long walk from the edge of the sidewalk to the wall of what is now Bliss Bridal, a shop at the corner of Main and Front Street.

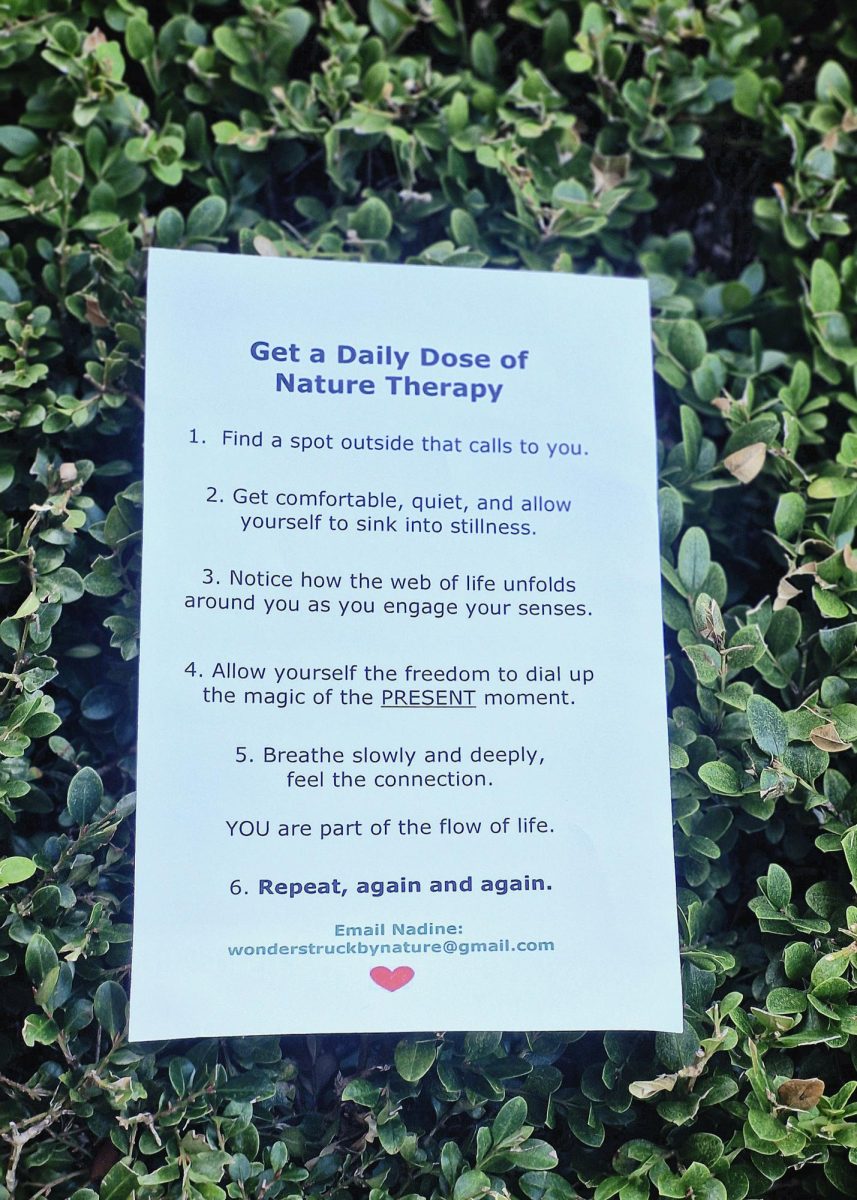

Photo by Caleb McCluskey.

These are Fairley’s fairly large footprints, and they mark the first memorial to African American life in Hattiesburg even though they did not start with that intention.

Southern Miss alumna Lisa Foster, who has a Masters of History with a focus on War and Society, said the footprints, which were cast in 1903, have been a mystery with many people not knowing they even exist.

“A lot of people don’t know about the footprints, and [people who do] don’t know they’re his,” Foster said.

Councilwoman of Ward 2 Debra Delgado said she was born and raised in Hattiesburg and never knew to whom the footprints belonged, but she used to play on them as a child by trying to step from footprint to footprint.

Foster said she is absorbed in Fairley’s story. Her research focused on Mississippi history and the Civil War, but her thesis was on confederate welfare. Although she currently works as a paralegal at Medley Law Group, she still researches his story.

But who was Fairley other than an African American man with an above-average shoe size? According to Foster, he was born a slave in 1840 and was respected in the lumber industry before he died in 1918. Foster said he joined the 74th Regiment United States Colored Troops during the Civil War and stayed a part of it until 1867.

Foster said she learned about Fairley while working on a speech about the Confederate monument in Hattiesburg. She said his footprints are the closest thing to not only a Union monument but also an African American Civil War monument in Hattiesburg.

Foster said no one can say for sure why Fairley’s footprints were cast, but that doesn’t excuse their importance to history.

“[Fairley’s] whole story is really a story of South Mississippi and how we are so connected,” Foster said.

According to Foster, she learned about Fairley through Charles Sullivan, a professor at Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College in Perkinston. She also said Sullivan learned about Fairley through a woman whose father knew him. Sullivan is quoted in two news articles between the ‘80s and early ‘00s about solving the mystery of Fairley’s footprints.

Foster said in the ‘80s, the City of Hattiesburg replaced the sidewalks downtown, and when they did that, they started wondering whose footprints were there. She said that local newspapers jumped onto the mystery, publishing stories about the footprints. Sullivan eventually learned that they were most likely Fairley’s, and the story ended. But in the late 2000s, he had to resolve the mystery.

Recently, the Stone County Enterprise interviewed Sullivan about the markers in Stone County, and he brought up Fairley.

“No one had heard of John Wesley Fairley, but I had. He was the most important black man of the 20th century and the late 19th century,” Sullivan said to Lyndy Berryhill of the Stone County Enterprise. “I had to do a lot of research on [W.P. Locker], but I had heard of him.”

Even though Foster has hours worth of news clippings and data on her computer and in a thick binder, which holds a picture of whom she believes to be Fairley, there are still a lot of mysteries left for her to uncover. Mainly, she wants to connect Fairley to a person living today.

Foster said she wants to formally ask the city to put up a marker in honor of Fairley, but she wants to find a relative of his to help advocate for it.

“I’ve been working with the city to get a marker put up for the footprints. I’m hoping to [get approval] pretty soon,” Foster said. “I’ve got to start looking [for Fairley’s descendants] again because I want them to be a part of this marker, once we get it going.”

During her research, she has connected Fairley lineage up to 1974 when a descendant died in a car accident, but she has been unable to get closer to the present.

Foster said stories like Fairley’s matter because we don’t often get to see records of African Americans, which makes genealogy hard for those who come from a background of enslaved people.

“It’s hard to find stories of slaves here because there weren’t that many [stories written down] compared to other places,” Foster said.

Fairley soon won’t be the only African American to leave his mark on Hattiesburg. Vernon Dahmer, an African American man who was killed in 1966 battling voter suppression, will soon have a statue downtown to memorialize him.

Dahmer’s son Dennis Dahmer said he is happy to see his father remembered with the monument, which was recently finished and will soon be installed as a centerpiece in the Forrest County Courthouse plaza being built.

Dahmer was attacked in his home by the Klu Klux Klan. He and his family were in their home when a group of klansmen torched his house. He helped his wife and young children out of the house, but he sustained fatal burns. Dennis Dahmer, who was 12 years old, was in the house during the attack.

Dennis Dahmer said the Forrest County Board of Supervisors approached his family, asking how they would feel about a statue of Vernon, and his family felt it was a great idea. Dennis Dahmer said his family will be happy with the installation as long as it tells the story of his father correctly.

“We appreciate whatever people decide to do as long as it is done in a positive manner,” Dennis Dahmer said. “We think it is important that the legacy be maintained in an accurate manner, and we are glad that this is something [The Board of Supervisors] decided they wanted to do.”

Dennis Dahmer said that his father’s monument goes to show the progression that both Hattiesburg and Mississippi have made since his father’s death. He said remnants of the past still overshadow the South, but that does not hinder the progress the state has made.

“The Mississippi of 2019 is considerably different than the one in the 1960s,” Dennis Dahmer said. “I saw [segregation,] and I lived it, so Mississippi has come a considerable distance from what it was.”

In part three, McCluskey will examine Confederate monuments, Forrest County’s origin and the controversies surrounding them.