When watching a movie or TV show, you know the character and their lines after the first scene. They crack stupid jokes and talk about food nonstop. Their romances are failures or nonexistent, and their physical movements are terrible.

They are the funny fat friend.

How often is the funny fat friend pushed to the side physically and mentally? Most of the time, which is kind of sad, considering how much they carry the script with comedic relief.

In media, the problem is not a character that is funny and also, coincidentally, happens to be fat. The problem is when being fat defines the characters and their narratives, such as Fat Amy from the popular “Pitch Perfect” movie series and Fat Monica from that one episode of “Friends.” Fat Amy literally referred to herself as fat before the other women could do the same. Fat Monica served no other purpose than to provide comedic relief and to act as light, zero-calorie character growth.

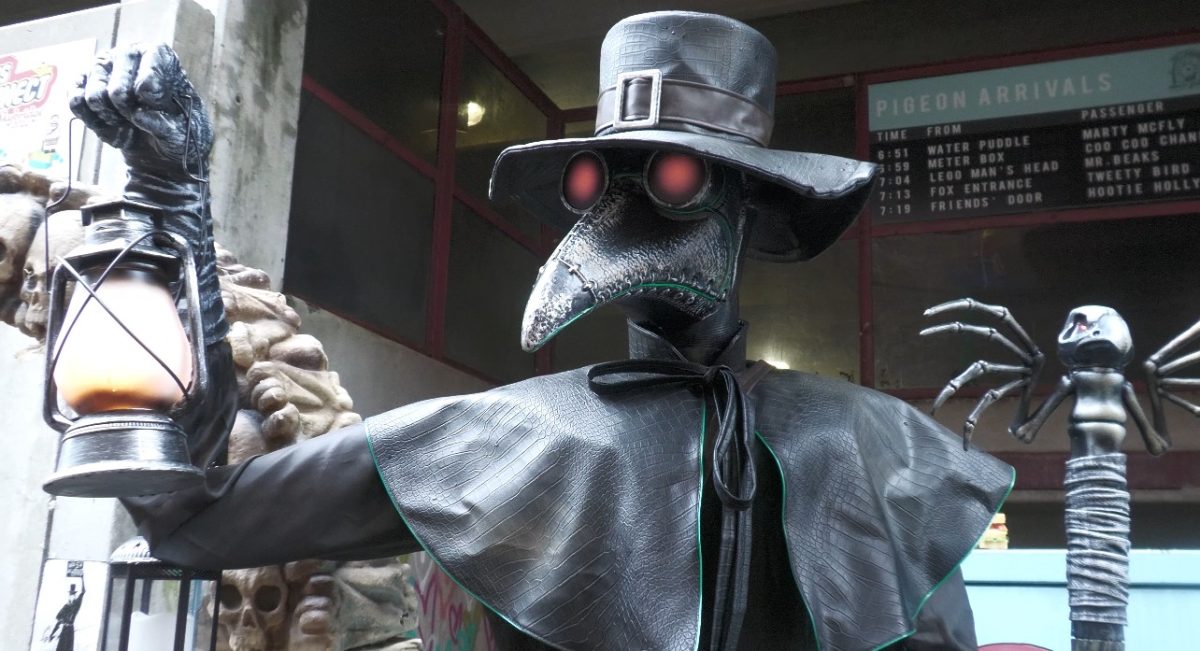

The most recent pop culture example is the upcoming “Cats” movie, starring James Corden and Rebel Wilson. Corden plays Bustopher Jones, a fat cat known for his peculiarities for food. Wilson is cast as Jennyanydots, whose most redeeming qualities are her absentmindedness and, well, being fat. While the fat characters are true to the original musical, this further proves how outdated the trope is.

Characters like Bustopher Jones and Jennyanydots are intended to be funny for the audience members who are not fat.

Rarely will there be a fat character whose entire arc is not designated by their weight. One of the better examples is Tiny Cooper, a gay football player in John Green and David Levithan’s novel “Will Grayson, Will Grayson.” Tiny’s narrative is driven by his sexuality and not his weight, which is a whole other can of worms.

The root of the problem with the funny fat friend stereotype is the belief that being fat is an automatic invitation for ridicule. It is the idea that being fat means being taken less seriously than skinnier peers.

While the problematic trope should have been abandoned long ago, nothing will change until the body types discourse changes. “Fat” is not, and should not, be a negative term. It should have the same neutral connotation as other adjectives like “tall” or “short.”

Why is it that scriptwriters are capable of writing anything, but continue to fall to old tropes and stereotypes that are ridden with mothballs like an old sweater? We grew up with the funny fat friend, and they are familiar and comfortable, but for all of the wrong reasons.

By providing characters that are fat but without dimension, Hollywood says, “Look at how inclusive we are! But not too inclusive. Just inclusive enough that you can’t be too mad.” It’s like Victoria’s Secret including only one model that is more than a size 2.

Scriptwriters and novelists can, and should, change the tainted media discourse by portraying different fat characters on both the big screen and television. How can we move forward without different characters as cultural cornerstones?