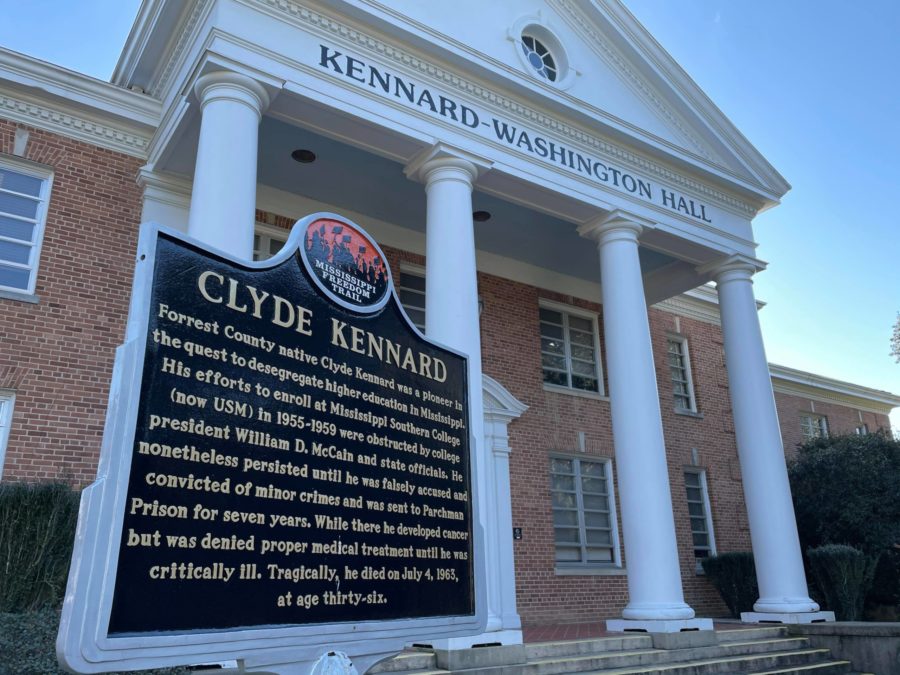

A person walking to Kennard-Washington Hall on the Southern Miss Hattiesburg campus might notice a historical marker on their way. The marker tells the story of Clyde Kennard, who spent years trying to desegregate Southern Miss. While that person can definitely learn about Kennard from the marker, one Southern Miss professor wants a much more extensive retelling of his life.

Samuel Bruton Ph.D., a professor of philosophy and the Director of the Office of Research Integrity, said the Kennard story had always moved him. Bruton wants to use his classes to build a digital humanities initiative, which would create a much more detailed retelling of Kennard’s life.

“Everything I know about the man impresses me[:] that he was an unusually admirable person, from his service in the military to his efforts to help out his mom,” Bruton said. “In many ways, he seems to encapsulate the many ethical values that I want my students to really understand and take seriously.”

Bruton said he wanted to take on the project because he believes Kennard’s story should be better known both locally and nationally. He said that, especially today, it is important to keep the history and issue of Civil Rights alive.

“The stories like Kennard’s and this poignant history [should be] kept alive,” Bruton said.

Kennard was born in Hattiesburg on June 12, 1927, and moved to Chicago to live with his sister. He served in the army for seven years and enrolled in the University of Chicago afterwards. Kennard eventually returned to Mississippi to help his mom run the family farm after his stepfather died.

Kennard wanted to finish his education, though, so he attempted to enroll at the University of Southern Mississippi, then referred to as Mississippi Southern College. Kennard was first refused enrollment in 1955 and again in 1959, being arrested after the latter attempt due to claims of speeding and illegal possession of whiskey.

Kennard was arrested again in 1960, this time on charges of burglarizing the Forrest County Cooperative. The actual robber, named Johnny Lee Roberts, said Kennard planned the break-in with no supporting evidence. Kennard was sent to Parchman Prison, where he was diagnosed with cancer. Kennard was released in the spring of 1963, dying shortly after on July 4, 1963.

In 1991, The Clarion-Ledger published Sovereignty Commision documents that showed Kennard had been framed. In 2006, another Clarion-Ledger reporter, Jerry Mitchell, further investigated the case, finally getting Roberts to admit that he had lied. Kennard was posthumously exonerated on May 17, 2006.

“For the average faculty member or student just landing on the Hattiesburg campus, you could spend a lot of time at USM without understanding or knowing much about Clyde Kennard and his story,” Bruton said. “I think every student and everyone who works [at USM] should understand that story. It’s an important part of our history and an important part of the legacy for this institution.”

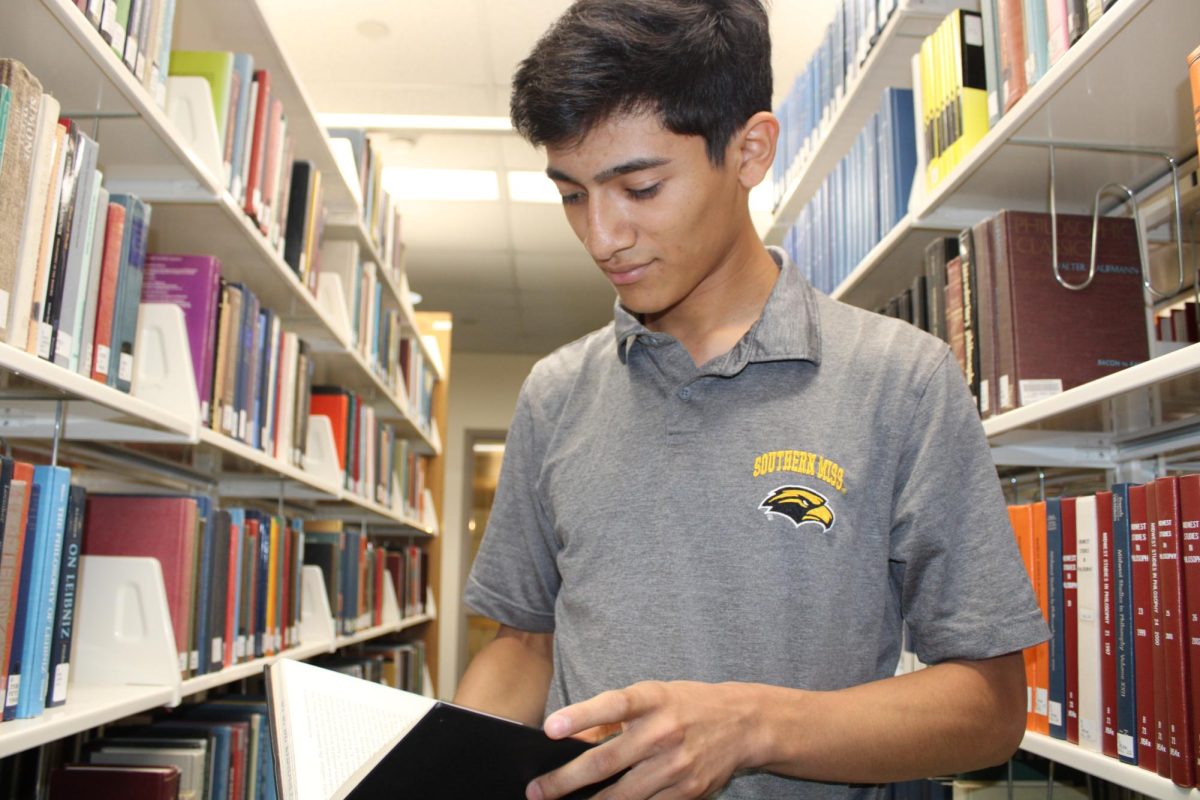

Bruton said that, while many parts of Kennard’s story are well known, there are still other parts that are not readily available. Bruton wants students to help him search the Mississippi Sovereignty Commision archives, find relevant passages about Kennard and bring the passages together in a common website. Bringing the findings together would make it easier for Southern Miss faculty, students and members of the general public to study documents relating to Kennard.

“The basics of his stories – you can access through Wikipedia and other sources – but there are still aspects to the story that can be usefully brought out,” Bruton said. “I want to engage my students in a digital humanities service learning project to explore these archive materials.”

He also wants for his class to seek out people in the community or around the country who had known or had a connection to Kennard. Bruton added that people outside of his class would eventually be welcomed to help with the project, but not at the outset.

“I am learning myself and going to have to learn as part of this effort how to do an Omeka website,” he said. “I will have to learn to do that and teach students how to work with Omeka tools, so I imagine it will take me a semester to understand how the process can be most effectively constructed.”

Bruton said he is expecting the project to take multiple semesters to complete. He imagines the website in sections, with certain parts being biographical, others detailing the trials against him and still others explaining the way Southern Miss was segregated at the time.

“I see this as an important way to educate my students, that the students would be involved in not just learning a bunch of stuff but to construct something with lasting value and meaning,” Bruton said. “I think that is something students would find rewarding and would be educational for them.”

The first semester this project will begin in the fall 2021 semester. Bruton wants his Philosophy of Law class to first dig into the legal details relating to Kennard’s conviction. He believes learning about the trials and conviction will be an engaging way to teach students about the law.

“Depending on the nature of the students in the class and the class focus, we might delve into a different aspect of the Kennard story,” Bruton said.

If any student is interested in working on the project, they can sign up for one of Bruton’s philosophy classes with help from their academic advisor.