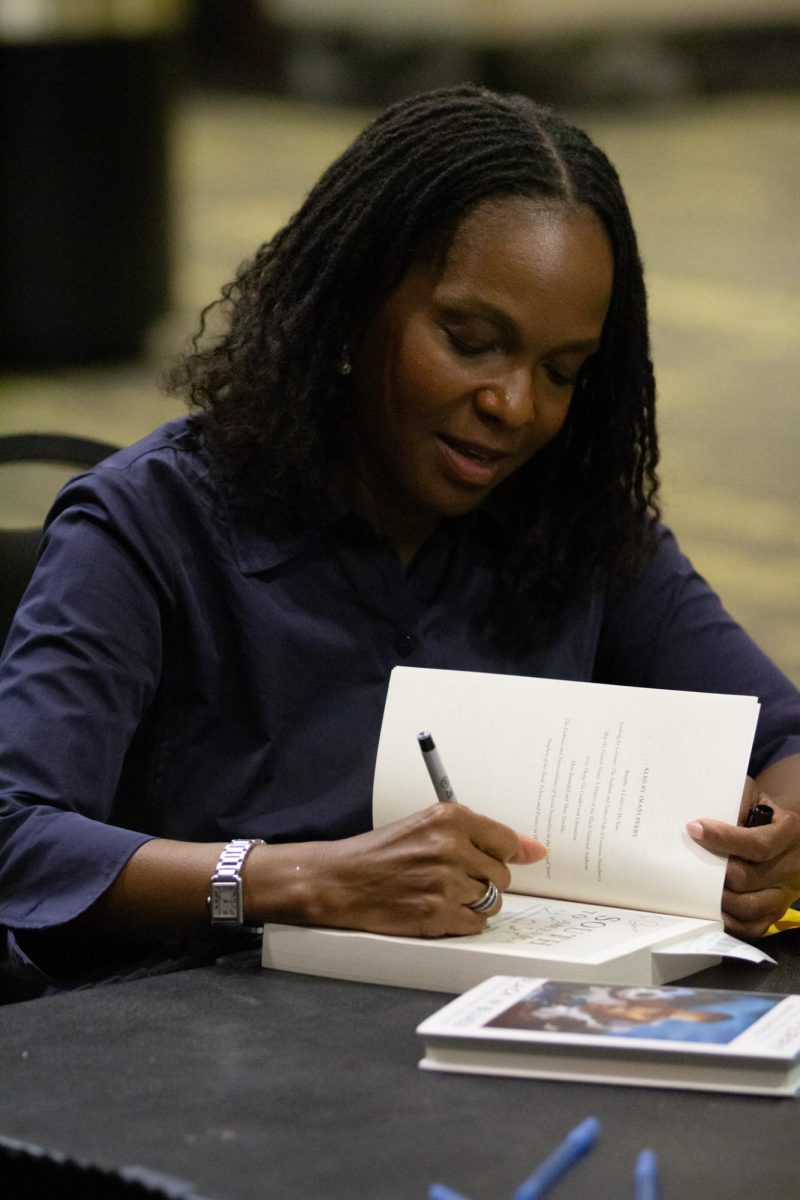

The University of Southern Mississippi began its annual University Forum series on Sept. 14 with a lecture from Jodi Kantor, one of the New York Times journalists that initially investigated allegations of sexual misconduct and assault from former Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein.

The Weinstein exposé, co-written by Kantor and fellow journalist Megan Twohey, is often cited as the spearhead for the 2017 #MeToo Movement. Though #MeToo officially started back in 2006 by activist Tarana Burke, the Weinstein story opened up a formal dialogue about sexual harassment in Hollywood. Multiple celebrities, including Alyssa Milano, Uma Therman and Terry Crews, shared their own stories of sexual harassment over the years, leading to increased calls for accountability both in and outside of Hollywood.

But the impact of Kantor and Twohey’s work is mostly apparent in retrospect. Kantor spent most of her lecture describing the uncertainties and roadblocks they faced while investigating the allegations, as, though many women had stories about Weinstein’s abuse, few were willing to publicly tell their story. Kantor and Twohey had no idea how the article was going to be received, especially within a climate that rarely punished powerful men for sexual abuse.

“That night in the cab [a few days before the article dropped],” Kantor recalled, “I remember Megan saying something to me like, ‘After all this work that we’ve done, after all the secrets we have discovered… What if nobody cares?’”

Before beginning work on the Weinstein investigation, Kantor had been a political correspondent for the New York Times. She had worked closely with Barack and Michelle Obama throughout his presidency, and even wrote a book about the two in the leadup to his reelection.

However, Kantor found her actual passion within investigative journalism, though it was largely by accident. In 2006, long before she began work with the Obamas, Kantor wrote an article about various class problems plaguing a lot of blue collar mothers. Specifically, Kantor wrote about the lack of access many working class mothers had to private lactation rooms, meaning they were unable to have the time or privacy to pump breast milk.

The actual impact of this article only came about seven years later, when Sascha Mayer emailed Kantor about the article. Mayer and her business partner read the article a little after its publication and began work on Mamava, a “freestanding lactation station” where new mothers had the ability to pump breast milk in a safe, private place. Mayer announced that the first Mamava station was going to be installed in Burlington airport, and Kantor was surprised — and delighted — that her work had led to actual change.

“[At the time, it] was such a slender little effort. It was one piece of equipment, and I don’t know if you have ever been to the Burlington, Vermont airport, but it is endearingly small. It looks like you are about to take off for a flight in your aunt’s living room,” Kantor said. “It was nothing. But it meant something to me, and, frankly, it spoke to me in a way that all those years of political coverage never had.”

Mayer’s email inspired Kantor to pursue other investigations in hopes of inciting real change. This was part of the reason why she took on the Weinstein story at all, despite the constant harassment and threats she got from Weinstein’s lawyers while working on it.

Kantor ended her lecture by reiterating her main point: we all have the power to incite change in the world, and that even private pain, when brought to light, can turn into collective strength.

“Let’s keep talking,” Kantor said. “And please, please, please, keep reading.”