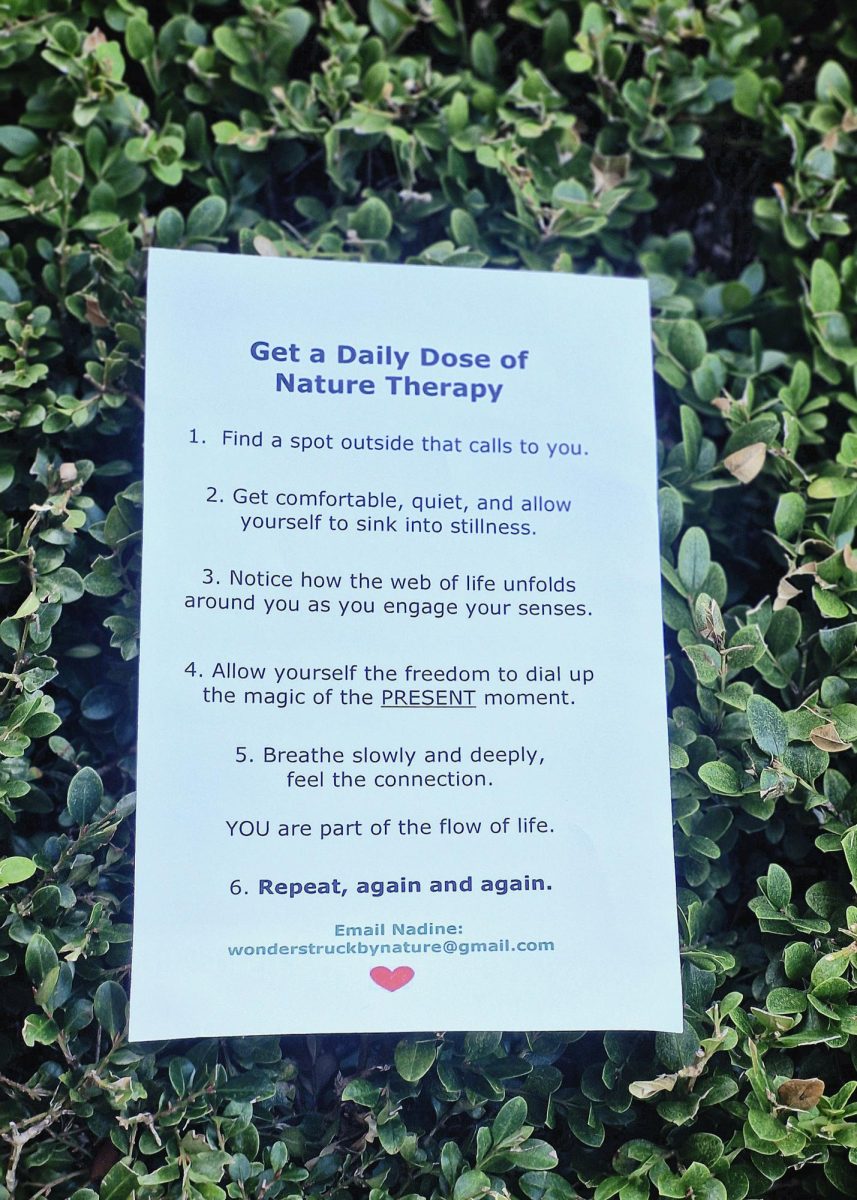

Photo by David Bundy

After facing violent protests in Kiev last February, Ukraine’s acting president, Oleksandr Turchynov, focused his attention on pro-Russian separatists in the East by issuing a 24-hour ultimatum on Sunday, April 13 for protesters to lay down their arms or face the wrath of Ukrainian troops and police.

According to The Los Angeles Times, the separatist groups did not comply and instead seized additional buildings in the town of Slavyansk, 90 miles from the Russian border, while facing no opposition from Kiev as threatened.

Turchynov promises that the “anti-terrorist operation” is under way but that it will take time.

“It will take place in stages, responsibly, in a considered way. I once again stress: the aim of these operations is to defend the citizens of Ukraine,” Turchynov told parliament.

Indeed, according to Newsweek, witnesses said armored trucks and military personnel were seen making their way north of Slavyansk on Monday, April 14 surrounding the city to reclaim it under

their control.

Russian President Vladimir Putin said Tuesday that this counter move by the Ukrainian government “essentially puts the nation on the brink of civil war.”

Turchynov said he is not against the possibility of holding a national referendum on May 25, alongside the presidential elections, to elicit a consensus on where Ukraine should stand politically.

Ukrainian Catholic University student Dasha Korin, 21, was born in Kiev and has lived in the Western town of Lviv for the past seven months to study journalism.

Photo by David Bundy

She said one of the things the conflict has brought is the fear of being separated from family and friends in the Russian-occupied Crimea. A civil war could make this separation more definitive.

“I know people from Crimea,” Korin said. “My godmother and my first cousin live there. We have very nice relations in spite of (the fact that) they want Crimea (to belong to) Russia.”

“(The) separation of Crimea upsets me so much. I love this place. I go there (each) summer, but now I don’t know if I want to go there this summer, if it’s safe to go there and if it’s possible to go there.”

Korin’s academic peers are among those who started the initial protests in Lviv.

“My university supported students in their actions, and it was first Ukrainian university which expressed its position about what is happening,” Korin said.

“They put a statement on the university web site. It (said that) they are against the government and support students.”

She says she directly felt the effects of the violence around her, as one of her university history professors was killed in February at the age of 28.

University of Southern Mississippi alumnus and photojournalist David Bundy was in Ukraine during the riots while he and his wife went through the process of adopting four Ukrainian children.

He described the violence that he and his family witnessed when the protests first broke out in Kiev.

“When the fighting was at its worst, when nearly 100 people were killed, we hunkered down in our apartment. The bombs exploding and gunfire had the younger children quite scared,” Bundy said. “Explosions rattled our windows and gunfire was heard for nearly two days solid. I had told everyone to stay off of our balcony, which faced the fighting after I heard two bullets zing overhead.”

According to Bundy, protesters closed their street with barricades to stop police, and their nearby markets were running out of supplies, such as bread and water. Their apartment was located between Independence Square, where the fighting was, and St. Michael’s Cathedral, where many wounded protesters were getting medical help in a makeshift facility.

Bundy said that after violence subsided in Kiev around Feb. 21, when President Viktor Yanukovych fled the country, he took his family out into Independence Square to observe the history that had just been made in the children’s home country.

“It was a solemn experience but made them proud of the protesters who fought for their freedoms,” Bundy said. “We encountered a memorial procession where one of the killed protesters was driven through the crowd in a hearse. The kids were visibly saddened and understood.”

Bundy reported that his new family is adjusting well to life in the United States and he hopes to enroll the children in school next August. He and his family recognize the reality of Ukraine’s current standing but foresee an end in the country’s favor.

“I think Ukraine is really on the brink of bringing itself out of Russia’s shadow,” Bundy said. “Many of my friends still think of Ukraine as part of Russia. Ukraine has an identity problem and they want more than anything to be free from their Soviet past, politically and economically.”

Lauren Persons was 23, nearing the end of earning her undergraduate degree in sociology, when a recruiter came to Southern Miss in 2010 and inspired her 27-month commitment with Peace Corps Ukraine.

She said through the relationships she made, she has truly witnessed the resilience of the Ukrainian people.

“All of my Ukrainian family and friends have been affected by the protest on either a physical or symbolic level,” Persons said. “While I lived there, government injustice and dysfunction were common topics of conversation. The fact that the people gathered in a collective effort to change something in their country restored a certain amount of hope.”