On any Sunday morning in Waffle Houses across the South, you’ll witness American democracy in action. Often, a romanticized version of democracy is presented, but Waffle House, with all its charm, is loud, chaotic, and serves everyone—just like democracy.

My first encounter with Waffle House took place during my freshman year at 2 a.m., when I had studied so long for my midterms that I forgot to eat. When hunger finally struck, my friends and I feasted on an All-Star Special with pecan waffles. Whether during late-night moments of friendship or Sunday morning breakfasts, Waffle House has remained a faithful companion. Last month, when Lana Del Rey released a sample of her unreleased song mentioning Ethel Cain and referencing “the most famous girl in the Waffle House,” the internet erupted into a messy debate over who gets to represent the authentic American working-class experience. Cain has long criticized Del Rey’s version of Americana as “peak opulence” while positioning her own art as a voice for people who are “constantly spat on.” Yet this pop culture drama feels absurd when you’re sitting in an actual Waffle House booth, where real working-class America unfolds daily.

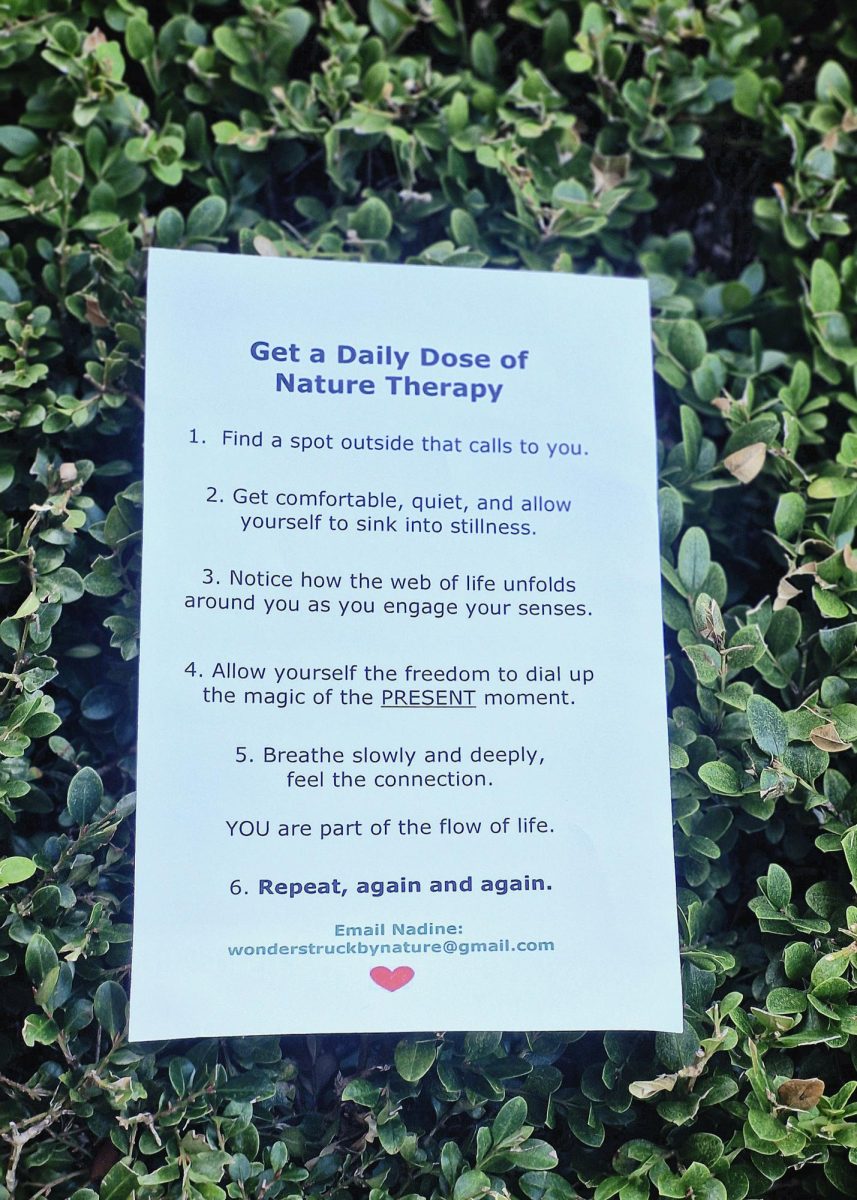

On the rare occasion that I can find a seat on Sunday morning, I feel most alive. In one booth, a grandmother dressed in church attire shares food with her grandson. Just a booth over, a group of college kids, hungover from Saturday night, debrief their weekend. At the counter, a shift worker sits next to me, heading home after a night of work. People of different ages, races, and classes all share hearty, affordable meals together.

This is what integration looks like—not the carefully curated diversity seen in corporate photos, but the organic mixing that happens when high prices, dress codes, and gatekeeping are removed. Waffle House strips those barriers away. You can come as you are, pay what you can afford, and get fed.

While coffee shops charge $7 for a latte, pricing out more than half the community, and restaurants require long waits and “smart casual” attire, Waffle House remains stubbornly accessible. The hash browns cost the same for everyone, regardless of political beliefs. The same fluorescent lights shine on all patrons equally. The same servers treat both the preacher and the philosophy student with the same blend of efficiency and warmth.

This democratic space exists because of workers who are among the most undervalued in our society. Servers earn $2.13 an hour plus tips; cooks make barely above minimum wage. Yet they’re the ones creating and maintaining this space of equality. They show up early, work doubles when someone calls out, and stay open during hurricanes when everyone else goes home. FEMA’s Waffle House Index literally uses the chain as a disaster measure because the workers are that reliable and essential to our society.

It’s about time we recognize that democracy doesn’t materialize in marble buildings on Capitol Hill but in yellow booths at 3 a.m. It unfolds as differences dissolve over the shared experience of being hungry, human, and in need of a warm, familiar place.

Waffle House succeeds where many institutions fail because it asks nothing of you except that you’re hungry. There are no membership fees, no cultural prerequisites, no performance of belonging required.

In an era of increasing polarization and segregation—whether economic, cultural, or political—Waffle House practices a radical act of inclusion. It proves that democracy doesn’t have to be perfect to be real, nor polite to be powerful.