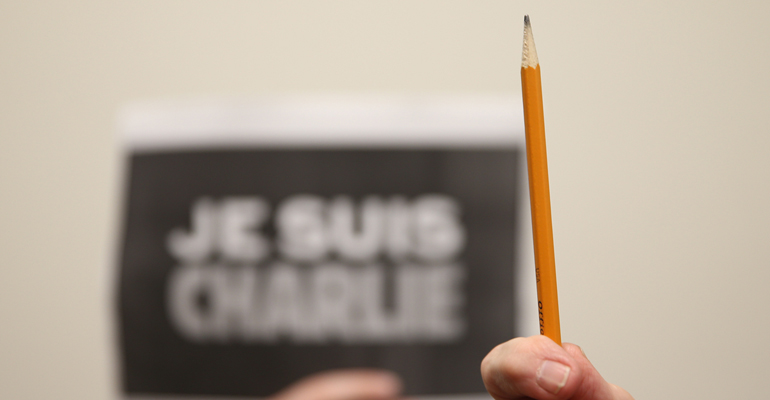

Photo illustration by Susan Broadbridge/Printz

It was a grim way to start the year for humanity. It was barely a week into New Year’s hangover recovery and a pair of brothers already found a way to put an early damper on 2015. They walked into the eastern Paris offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and killed writers, editors and cartoonists who were in a staff meeting, as well as two police officers. It was the deadliest attack France has

known in decades.

As if Internet users had not seen enough horrors in 2014, a video of the men shooting a wounded police officer before driving away quickly spread through the web. French President François Hollande called the shooting a “terrorist operation,” in which the members of Charlie Hebdo were “cowardly assassinated.” The whole world looked as the reactions and pursuit that followed received heavy coverage from an array

of news organizations.

I will not spill more ink on the series of events that occurred in the following two days and led to the death of the attackers, because the offenders don’t deserve the attention they claimed in the most ignominious fashion. They should remain faceless manifestations of inhumanity that history will treat as a bad memory that underlined the importance of crucial values like freedom of speech and expression, rather than established a reign of fear and silence.

The true martyrs of this nightmare are the cartoonists, columnists and other members of Charlie Hebdo whose premature demise sparked a wide reaction in France and around the world, and whose names will be remembered far longer than those of their executioners.

“I’d rather die standing up than live on my knees,” Charlie Hebdo editor Stéphane Charbonnier famously said in 2012, in response to threats after the magazine published depictions of

the Prophet Mohammed.

Thousands decided to stand up as well, gathering on Paris’ Place de la République hours after the attack, to pay tribute to the journalists, showing a rare sense of national unity. “There (was) a feeling of togetherness,” said NPR’s Eleanor Beardsley. Social media flooded with hashtags and tributes, “Je suis Charlie” (I am Charlie) logos blossomed and soon the work of cartoonists around the world who illustrated in many ways their grief and expressed the absurdity of the event circulated. U.S. President Barack Obama talked of the “horrific shooting,” and offered his assistance “to help bring these terrorists to justice.”

U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said the attack was “a direct assault on a cornerstone of democracy, on the media and on freedom of expression.”

Critics pointed out the dubious or questionable direction taken by the magazine in recent years, allegedly falling from intelligent satirical content to gratuitous provocation following previous threats from Muslim radicals.

The argument, worth hearing and discussing, was what keeps me from jumping on the “I am Charlie” hype train and rush to idealize the satirists as holy symbols of liberty. Nevertheless, none could remain a cynic facing the atrocities committed in the name of misleading religious ideals in direct opposition with a free, open and cultivated society.

Moving forward, the key to a healthy recovery is to avoid getting caught up in the excitement of the frivolous uses of the tragedy to senseless ends like the heavy politicizing of the issue or making money off “Je suis Charlie” memorabilia. But most importantly, it’s central to avoid committing amalgams with a Muslim world that has already had its share of profiling and hate in recent years, much too easily confused with the violent criminals who proclaim their actions to be in the name of Islam. Pointing the finger at Islam after the attacks only shows a poor understanding of radicalism, of the Muslim faith and its community.

But if the age of information has brought new tools to radicalism and given birth to terrorism by allowing minor ideas to be heard across the planet thanks to the exposure of violence rather than to healthily grow, mature and properly spread through debate and discussion, it has also brought people together in their common faith in basic human values.

Despite grief, profound sorrow and despair, the most transcending human feeling expressed throughout this gloomy page of history is hope.

Hope is what drove the thousands of people in the streets of France this past week. Hope is what kept Charlie Hebdo cartoonists joking and drawing in the face of threats. Hope is what will encourage people to express themselves and openly debate ideas in peaceful ways, refuse to cave in front of violence and obscurantism.

The day after the attack, former Charlie Hebdo publisher Phillipe Val said in a radio interview that he had lost all of his friends that day.

“We cannot let silence set in, we need help,” Val said. “We all need to band together against this horror. Terror must not prevent joy, must not prevent our ability to live, our freedom and expression.”