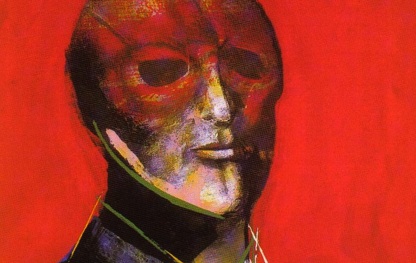

“American Psycho” by Bret Easton Ellis is a homicidal roller coaster that, while disturbing, may be one of the most brilliant pieces of literature of its time.

My friend Katie loaned me the novel and I ripped into it voraciously, having thoroughly enjoyed the movie. The film, starring Christian Bale as leading man Patrick Bateman, was a fascinating satire about the yuppie culture of the ‘80s and an exploration into the age of excess.

Bateman is a successful businessman on Wall Street with a large apartment in Manhattan. He dines at fabulous, trendy restaurants. He enjoys pop artists such as Phil Collins and Whitney Houston. He is incredibly attractive and has a beautiful girlfriend. Not to mention, Bateman is also a psychopathic serial killer.

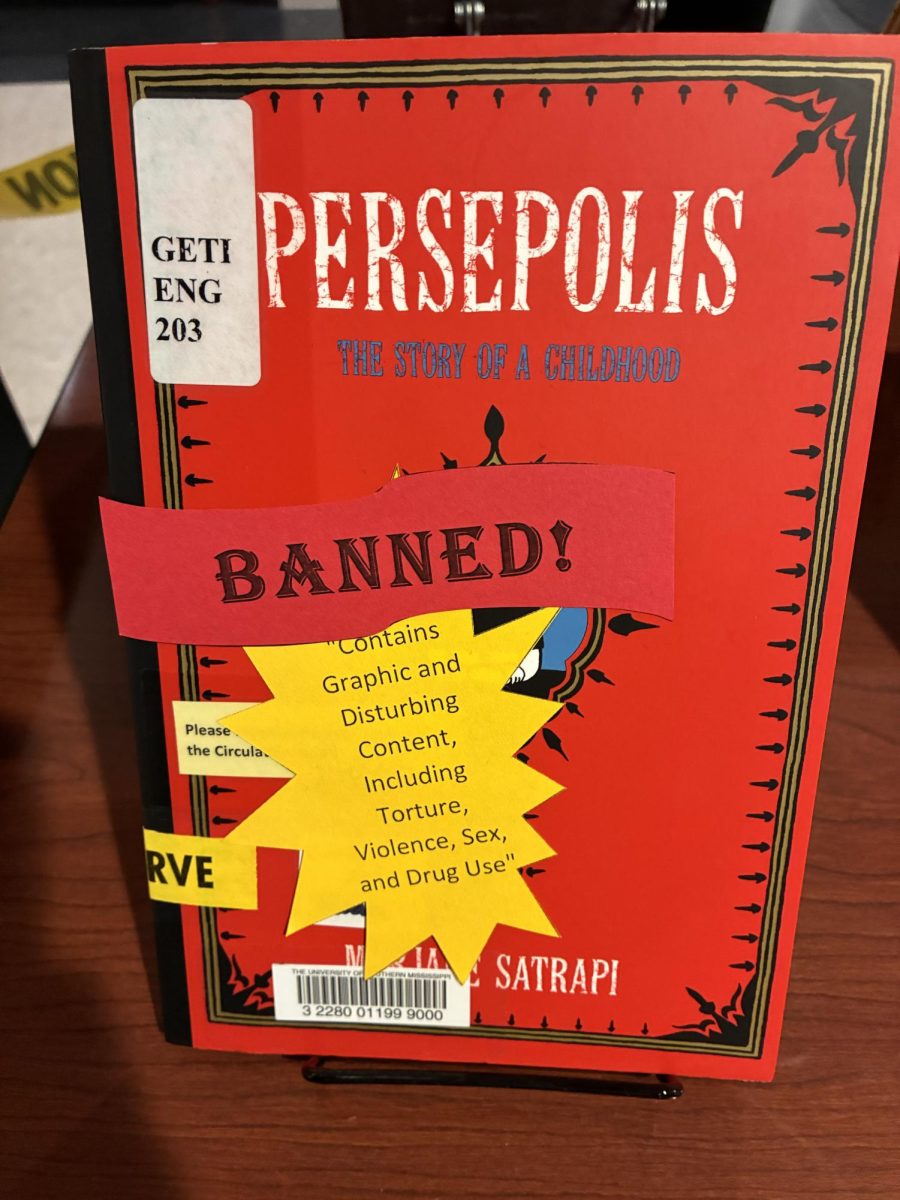

While I have developed certain desensitization to grotesque violence due to my fierce love for Chuck Palahniuk novels, “American Psycho” brought discomfort to an entirely new level. With pornographic-level violence and explicit depiction of sexual scenes, Ellis uses a sharp contrast with the dull everyday life of Bateman to bring a particular form of horror to the reader.

Patrick Bateman as a character is one of purposeful ambiguity. He is often mistaken for other businessmen and other businessmen are often confused with other people – an intentional choice by the author to add a touch of humor and to take away the face of Bateman and his comrades.

He is particularly attentive to fashion, knowing explicitly the designer of the majority of the clothing worn by the people around him. This choice, while tiring to read, is particularly interesting to the dynamic of the story.

Listing the designers of the clothing not only gives an idea of the disproportionate wealth of his Wall Street companions, but it provides a sense of Bateman’s misguided superiority when faced with a person on the street such as a homeless man or a busker who wears no name clothing.

This inherent attention to detail runs throughout the story until around the middle, with hints at the darkest desires of Bateman’s heart. Ellis then begins Bateman’s descent into the depths of his dementia, where he eventually goes on a killing, dismembering spree. He also dabbles in cannibalism, which he mentions lightly in passing over drinks with his friends.

While violent, disgusting displays of crazy can be fun, what made this novel remain in my mind is the way the author makes his thematic points and his mastery of the language.

One famous quote from Bateman said: “There is an idea of Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can sense our lifestyles are comparable: I am simply not there.”

This one line sums up the theme of the novel and rounds out the gripping satire that Ellis wanted to point toward the vapidity of ‘80s yuppie culture. His ideas and themes shine brightly amid the blood and gore, making the reader question Bateman’s morals as well as their own.

This novel, for me, was a revelation. By the word “revelation,” I mean a piece of literature that I am proud to have read, but will probably never, ever read again. While Ellis’ command of language was commendable, the pornographic nature of the violence was simply too much for my personal tastes.

I would recommend “American Psycho” to the brave souls with different tastes and a strong stomach. For those who love a good satire mixed with horror-movie gore, definitely check out the film adaptation, because Bale shines as Bateman and many of Ellis’ themes are still prevalent on the silver screen. But, whatever happens, this is not a film to watch with the parents.

Bateman: “All I have in common with the uncontrollable and the insane, the vicious and the evil, all the mayhem I have caused and my utter indifference towards it, I have surpassed. Yet, I am blameless.”

Despite the blood and gore, “American Psycho” promises to be a satirical masterpiece that will stand the test of time.