In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education ruled segregation unconstitutional at public schools Clyde Kennard, a black Korean

War veteran, attempted to enroll at what was then known as Mississippi Southern College and was rejected three times. Kennard would not give up, so he wrote letters to the local paper pushing for educational integration. For that, Kennard was arrested twice on out-of-context criminal charges for which he was convicted and sentenced to seven years in jail. The college’s fifth president and state archivist William David McCain was hired in 1955 and tried to further develop Mississippi Southern College.

McCain tried to keep Kennard out of the college. During his trip to Chicago, McCain tried to sway the business community to make investments in the state of Mississippi. He attempted to keep talk of integration at a minimum, but he mentioned to business men that African Americans who wanted to desegregate schools in the South were Northerners. Kennard, however, was a Hattiesburg native. Kennard was battling terminal cancer and was eventually released on parole in 1963. He died six months after his release.

According to the Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage at The University of Southern Mississippi, McCain said, “We insist that educationally and socially, we maintain a segregated society. In all fairness, I admit that we are not encouraging Negro voting,” he said. “The Negroes prefer that control of the government remain in the white man’s hands.” Mississippi felt nationwide pressure to integrate as the rest of the country’s institutions were integrating during the early 1960s. McCain made his objection to integration apparent.

He was opposed to having black students enrolled at Mississippi Southern College. Again in Mississippi, another African American attempted to enroll at a university. In 1964, James Meredith was accepted to the University of Mississippi, although riots raged across the region as a result.

Ole Miss and Mississippi State University were both integrated by 1965 after enduring major opposition and violence from the white public. By then, The University of Southern Mississippi was pushed to integrate. Plans to accept the university’s first black students were in progress.

To protect the prospective students, faculty members were instructed to support the students with the transition, and the campus police department was told to prevent and stop any riots, protests or other acts against the two black students, Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong and Raylawni Branch, who enrolled in September 1965, according to the Southern Miss Alumni Association. USM recruited and encouraged students, political leaders, fraternity members and athletic members to ensure a calm environment on campus.

Since the 1960s, the university continued to transform and flourish by the day: online classes were implemented, the School of Nursing was considered a college, the university became affiliated with Conference USA and the Mississippi Polymer Institute was created.

September’s historical significance marks the 50th anniversary of desegregation at USM, which is why commemoratory events will be held on the Gulf Coast campus and in Hattiesburg. The 50th anniversary of desegregation at The University of Southern Mississippi will be held Sept. 2-6 and will include Soledad O’Brien’s keynote address. Raylawni Branch and Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong achieved a milestone the university is proud to claim, and students continue to change and expand the university.

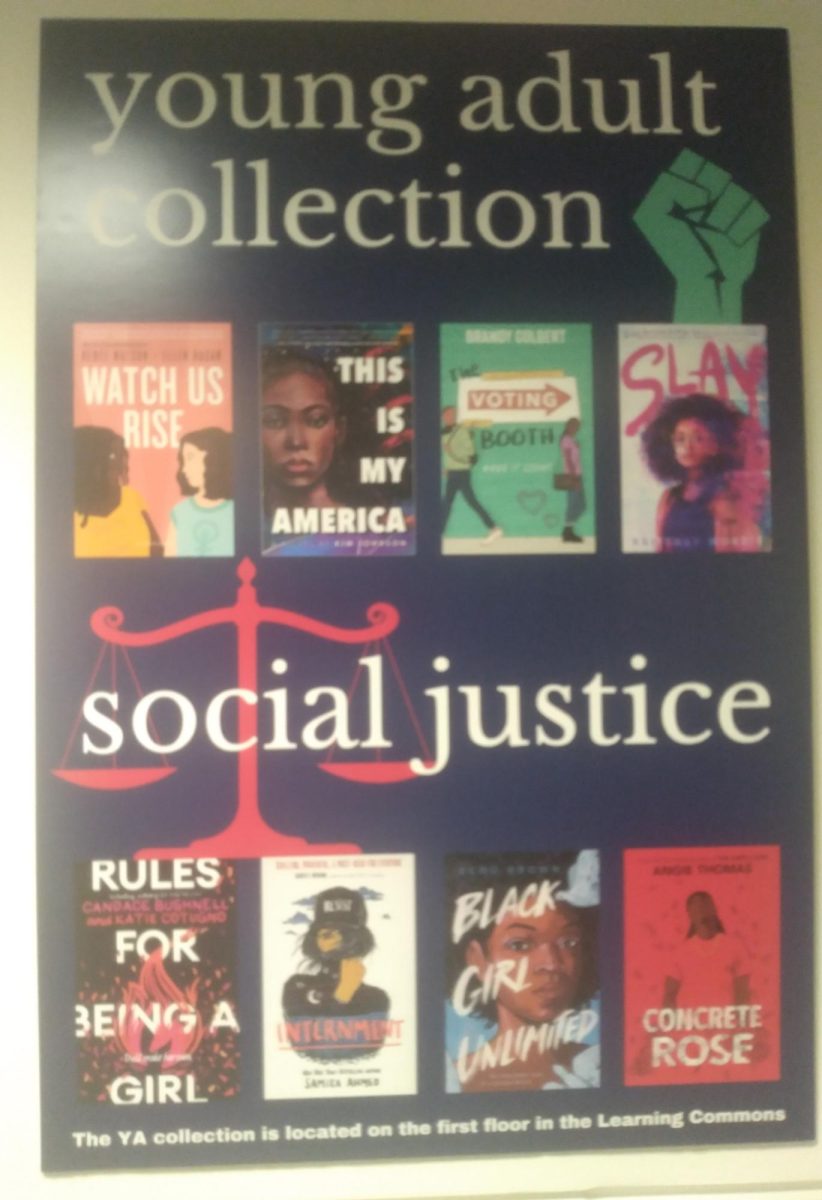

The school’s growing diversity continues today with 37 percent of the student body being made up of minorities. Southern Miss is home to 17 predominately African- American student organizations, academics enliven opportunities for African Americans through the Southern Miss Center for Black Studies and the Southern Miss Alumni Minority Constituent Society and the university provides annual changes for black alumni to network and continue to contribute to the Southern Miss community.