A group of marine scientists at the University of Southern Mississippi recently completed an expedition attempting to find the long-lost shipwreck of a vessel sunk in the Gulf of Mexico during World War II.

While the team did not end up finding the SS Norlindo, they did find new information they believe will help them continue the search for a long-lost piece of history.

Research Associate Professor Leonardo Macelloni operated as the Chief Scientist for the first part of the expedition and focused on analyzing data from the search. Macceloni and other researchers teased the idea of searching for a shipwreck for years, but finally got the funding this year to go search for the vessel.

“I had never been able to discover a wreck,” Macceloni said. “I was very excited about this project because searching for a wreck on the seabed is like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

Maccelonli and a team of 16 other researchers from Southern Miss and other institutions set sail Aug. 18 for the search area from USM’s Point Sur in an attempt to find the Norlindo.

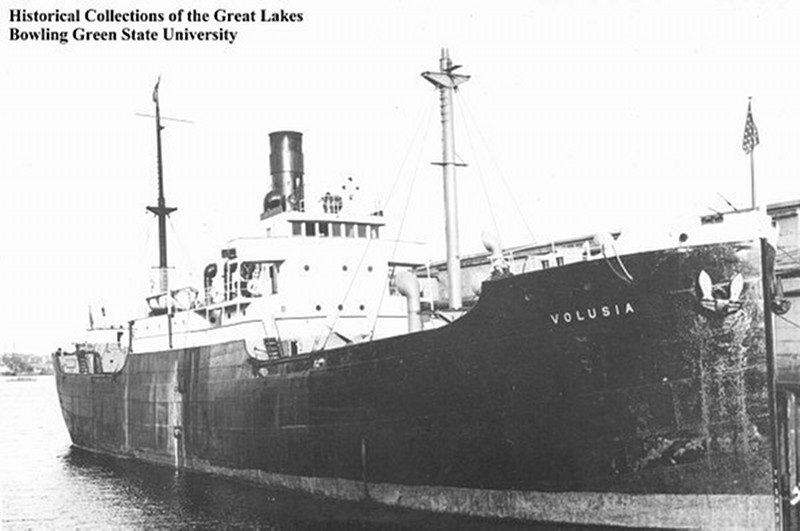

The Norlindo isn’t just any shipwreck, either. The vessel marked the first casualties in the Gulf of Mexico during World War II. In 1942, German submarine U-507 fired torpedoes that sank the Norlindo, a vessel carrying approximately 5,000 barrels of oil to Allies in Europe. 23 people survived but five died on board. 79 years after its demise, the vessel remains lost at sea.

The attack spurred the “Second Happy Time”, a period of German assaults on American vessels near the mainland. During the eight-month period, German U-boats sank 609 Allied ships, while only losing 22 U-boats.

“In the aftermath of it, the newspaper in Galveston ran the headline, ‘Wake Up Galveston’,” Douglas Bristol Jr., Gen. Buford Blount Professor in Military History, said. “There were rumors of enemy submarines in the Gulf before but this time, [with the Norlindo] there’s no doubt.”

Bristol said that the Norlindo’s fate, along with the other 608 boats lost in WWII, served as an important lesson for the Allies in the War.

“It’s not a foregone conclusion the Allies would win the war, but the reason they did is they learned as they went along,” Bristol said. “They learned how to come up with an effective convoy system, they learned tactics like blackouts and then they applied it consistently throughout all the theaters of operation.”

Macceloni also realized the lasting significance that the Norlindo had beyond scientific research. While at sea, a family member of a lost relative on the Norlindo contacted him and told him what the search meant to his family.

“When I got this email, I got goosebumps,” Macceloni said. “For many years, their family was trying to find out what happened to the Norlindo because they always wondered where their uncle was. [The Norlindo] is a graveyard. It’s very sensitive, so I was touched because, in addition to science, there’s something that touches the lives of people that were involved in this.”

Before Macceloni and his team sailed into the Gulf of Mexico to search for the Norlindo, they had to find out which “haystack” to look at first. His team relied on the historical coordinates from U-507’s captain.

Their research revealed a different and deeper position than the team originally thought the Norlindo was last located. Using the coordinates, Macceloni and his team narrowed the search area to a ten by ten-kilometer square.

Because of the depths Macelloni and his team were observing, the team had to use an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) to scan the area. The navigation system reports the vehicle’s movement data and the echosounder acoustically “illuminates” the seafloor, revealing the structure of the area it is passing.

Max Woolsey, an engineer on the expedition, operated Southern Miss’s AUV, the Eagle Ray.

“If the Norlindo had been within a 150-meter wide swath of seafloor as Eagle Ray surveyed along its trackline, we would have seen a characteristic hull shape and strong acoustic amplitudes returned in contrast to the softer returns off a muddy seafloor,” Woolsey said.

Hurricane Ida disrupted the crew’s expedition as it moved through the Gulf of Mexico. Though the crew was able to return to the area to scan again, they were unable to find the Norlindo. However, the crew did discover that the map they were using did not give them a “full picture” of the area they were searching for.

“We didn’t find the Norlindo, but we found that this [area] is a much more severe cliff than it was known to be,” Macceloni said. “That is important because[,] geologically speaking, this kind of situation is only caused by a major fault or other phenomena [that] are important to understand.”

The cliff area the crew searched in had a greater depth than noted, as Woolsey deployed Eagle Ray to depths of 1,200 meters.

Using this new knowledge, Macceloni hopes to not only research the area more, but also to continue the search for the Norlindo. Macceloni said his team is currently focused on obtaining more funding to continue the search so they can sail again as early as December.