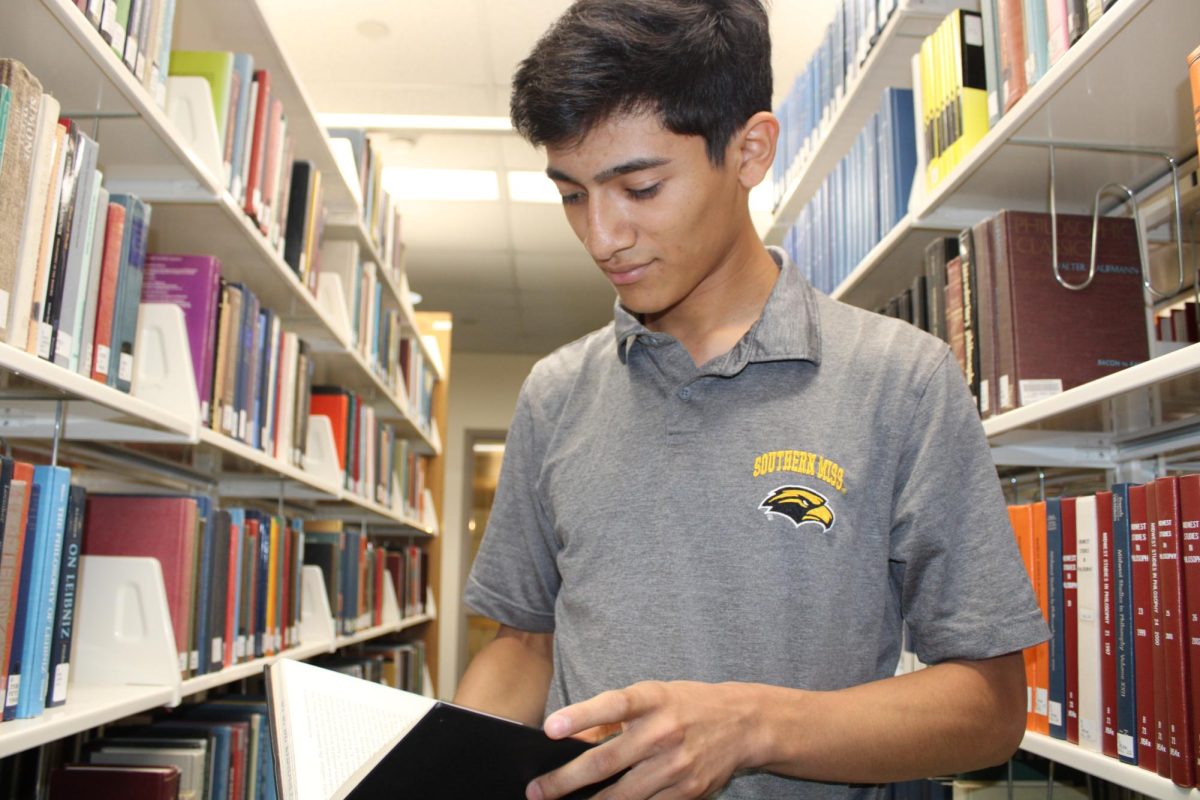

On any given weekday afternoon, you will find the University of Southern Mississippi’s beach volleyball team hard at work on their brand-new sand volleyball courts located on the northern edge of campus. However, on any given morning or early afternoon, you will find team members packed into a tiny office in the Academic Enhancement Center located under M.M Roberts Stadium. The office belongs to the Associate Athletic Director and Director for Student Academic Enhancement Program, Kylie Amato, who also serves as the volleyball and beach volleyball academic advisor.

Amato’s willingness to help others and loyalty to listen to her athletes are among the many reasons why her office is filled with students throughout the school day. Girls spread out on the floor doing homework, while others sit in chairs seeking advice from “Ms. Kylie,” as they call her. In addition to the herd of girls crammed inside Amato’s office, thank you cards, sticky notes with encouraging words and personal photos line the computer screen and walls surrounding her desk. Even the whiteboard in her office reads “I love you Ms. Kylie” and “We love you!”

If you were to ask any of the volleyball players, they could not imagine their college experience without Ms. Kylie. For Amato though, six years ago she was not sure she would still be living.

Amato has suffered from an eating disorder since she was in college. She developed her eating disorder while attending and playing volleyball at the University of West Alabama.

“As a volleyball player having to put on spandex and a spandex top and literally be glued into my uniform and have to go out in front of public and in front of boys, I did not feel like I looked like everyone else looked” Amato recounts. “I felt chubby.”

As a result, Amato began restricting calories, excessively exercising and eventually became bulimic. In her attempt to achieve the perfect body, Amato worked her way down to weighing just 102 pounds.

“You could literally see every bone in my neck, in my shoulders, in my back, in my ribs,” Amato said. “My cheeks had sunken in. My eyes had turned dark.”

She struggled with the eating disorder for ten years until people began to notice. It was after her parents and friends addressed her disorder that she was able to seek medical assistance.

Amato was then told by the doctors that she was one organ away from shutting down.

When Amato heard this and was also told that her life expectancy was short and her ability to recover was unlikely, she set out to prove them wrong. She began attending counseling sessions and was able to put on some weight to return to a healthier physical state.

“When I started putting on the weight, it was hard,” Amato admits. “I struggled and I still struggle with it every single day.”

The battle with her eating disorder is an ongoing affair for Amato. However, she now has support systems, such as family, friends and counselors, that she can speak to when having a trying day, an arrangement she didn’t have during her most challenging years.

Amato states she hid her condition from friends and family for ten years because she “felt like she had to keep it a secret. I didn’t think I could fail at something. I had to be perfect.”

The pressure to be flawless in sports, school and life, in general, is a widespread self-expectation that is present among many athletes and individuals who are involved in sports.

“Whether you are an athlete, you are a coach or you are an administrator, we work in a field where you are expected to be perfect,” Amato said. “You are expected to win games. You are expected to have good grades. You are expected to be the best of the best.”

This impossible standard can manifest into negative body image and eventually an eating disorder.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association found that the college athletes are vulnerable to developing eating disorders due to the high amount of stress they experience from adjusting to the demands of college, balancing school work and striving to perform in their sport.

On top of a busy schedule, revealing uniforms, athletic and societal body image, excessive exercise and healthy eating are also all stressors that contribute to a high frequency of eating disorders among athletes. According to the National Eating Disorder Association, in 2018, over one-third of female college athletes reported symptoms that put them at a high risk of developing anorexia nervosa.

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse also reported that 58 percent of female college athletes are at risk of developing bulimia nervosa. Male athletes are also at risk of developing eating disorders, with 10 percent capable of becoming anorexic and 38 percent at risk of becoming bulimic.

Due to the high correlation between eating disorder and athletics, Amato pays very close attention to the soccer, volleyball, basketball and golf athletes she sees on a daily basis.

“Because of my eating disorder and because I’ve had it for so long, it is easy to point out when someone else has one or someone is developing the symptoms of what goes into having a full-fledged eating disorder,” Amato shares. “I don’t want anybody to ever have to go through or suffer what I went through.”

The role of an academic advisor is to assist their assigned student-athletes in communicating with their professors, creating their class schedule and holding them accountable for their grades. For Kylie Amato, her job as an academic advisor extends beyond assisting with academics though.

“If you get into this business to just be an academic counselor then you are going to miss out on the true meaning of what you can really get out of this job,” Amato said. “I’m very personal and I care about my student-athletes, whether it’s the ones I work with on a day to day basis or it’s another athlete who comes in here and says ‘Ms. Kylie I just need to come and cry,’ or ‘Can you pray with me?’ or ‘Can we just talk?’.”

Amato intentionally pursues these trusting relationships with her athletes and has worked to manufacture the open environment that her office has become known for. Her main goal in life is to help others. In fact, she has earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology as well as master’s degrees in both sports’ administration and school counseling and guidance due to her strong desire to make a difference in the lives of others. Amato also aims to be a dependable and reliable source that athletes can openly share their struggles with.

Recently, Amato has extended mentoring outside of her office and has started to speak in front of Southern Miss athletic teams about her personal story as well as advice on how to handle the pressures of athletics. At first, she was hesitant about opening up about her struggles in front of her athletes, but now she finds it beneficial for herself as well as others.

Amato predicts that she will speak in front of a few more Southern Miss athletic teams in the coming semester. She has also reached out and volunteered to share her story with upperclassman at Petal High School about mental health, mental health awareness and eating disorders.

“Talking about it has actually been therapeutic for me,” Amato said. “I get to talk about how far I’ve come. If I can tell a group and it makes a difference too, then I’ll continue to tell the story.”