Letter of identity: The Wes Shaffer story

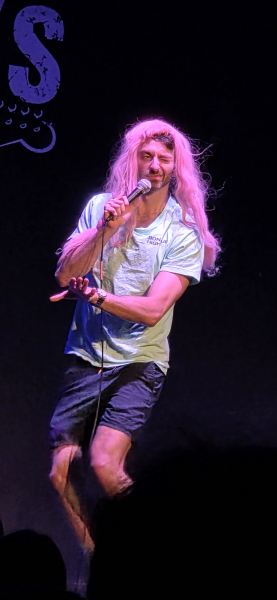

Wes Shaffer, coordinator of PRISM, the LGBTQ center at the University of Southern Mississippi, and USM Ph.D. student.

The world spun while they stood on top of the electrical box surrounded by thousands of people with every identity imaginable. Women with short hair, people of different races and ethnicities, individuals with various sexualities and nearly limitless possibilities danced and drummed at the heart of downtown Chicago for its St. Patrick’s Day parade. It was so much variety, in fact, that it sprung a panic.

Wes Shaffer, coordinator of PRISM, the LGBTQ center at the University of Southern Mississippi, and USM Ph.D. student, grew more into their nonbinary gender identity and gay sexuality after experiencing that crowd during freshman year of college. But discovering that identity created some unique challenges, and today, those challenges for members of the LGBTQ community are becoming even more difficult to overcome.

In the United States, 469 anti-LGBTQ bills have been introduced in 2023 to legislative sessions around the country, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. For those such as Shaffer, these bills reflect the harsh reality of present politics. In addition to difficulties such as adjusting to college, moving away from home life and gaining independence, LGBTQ youth rights are being balanced in the hands of the states.

“The fish rots from the head down,” Shaffer said. “It always starts from our leadership.” In addition to their responsibilities as coordinator of PRISM, Shaffer is involved with the International Development Doctoral program at USM, and understanding the impact of these bills and their language is vital to Shaffer’s work.

Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves signed an anti-trans bill into law in February. Known as the REAP Act, the bill prohibits puberty blockers, hormone therapy and transgender procedures for minors. According to Shaffer, these acts lack consideration of a myriad of different scientific knowledge.

“They’re not even light to 30% of the population…We’re just singling out individuals,” Shaffer said. For intersex individuals and those that live with hormonal imbalances, the REAP Act completely blocks Mississippians from gaining treatment in-state until they are 18 years old.

For Shaffer, they began questioning their identity before then. Shaffer grew up in the small farming community of Tipton, Indiana with their mother, father and brother.

When Shaffer was young, it was a town where everyone knew everyone. Different grades in the local school were all connected by one long hallway, and the predominant lifestyle, according to Shaffer, was rather heteronormative.

Men worked in fields and women ran the house. But for Shaffer and others who fit outside the traditional roles, the fight to gain a place was long, especially when born into these norms.

“I got kicked out of the Boys and Girls Club for taking my shirt off,” Shaffer said. They played sports with the boys and worked on farms and did housework. It was clear their identity was different, but no one else around them allowed further understanding or support, especially their family.

According to Youth.gov, which was formed out of multiple federal departments and agencies to promote healthy outcomes for youth, family acceptance of LGBTQ members is vital for those

individuals to navigate the stigma, isolation and even bullying that may come with identifying as such. Unfortunately, Shaffer was not afforded that support.

Shaffer’s father was a narcissist who slept most of the day because of late work shifts, and their mother suffered from anxiety and depression. “We had fend-for-yourself nights,” Shaffer said. “And fend-for-yourself was every night.” From seventh grade onward, Shaffer said it was up to them to figure life out.

Though they became self-sufficient out of survival, the darker aspects of their home life still haunt them. Shaffer developed post-traumatic stress disorder after being physically, mentally and sexually abused during their childhood. Even today, they still wake up in tears, crying from nightmares of being in the same room where the sexual abuse happened.

Shaffer’s early trauma dramatically impacted their understanding of their gender identity. Their family’s attitude toward LGBTQ people was overwhelmingly negative, and the harsh stances against members of the community led to Shaffer’s own internalized homophobia.

In high school, they entered their first gay relationship. “I loved her, but then I was like, ‘I’m still going to marry a man,’” Shaffer said. They said their lack of self-acceptance was based on their family’s ideas about sexuality.

These stigmas and fears associated with LGBTQ identities play a large part in coming out, especially for youth and younger people. According to a 2015 Princeton University study titled Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples, historically, social stigma with identifying as LGBTQ made people come out later in life.

For Shaffer, they waited until three or four months into college at Elmhurst University before telling their immediate family about their queer identity. “I wrote a letter out of fear because I knew if I told them to their face,” Shaffer said, “I might not be here today.”

The handwritten letter marked Shaffer’s honesty with not only their family, but also, with themselves. Using the last bit of strength Shaffer had at the time, their family responded with nothing but silence.

With family support completely gone, the people around Shaffer stepped up to become a found family.

The basketball team Shaffer was on consisted of tightly-knit players who enjoyed the fun scenes of Chicago. “It was like I had the whole family that I needed right there,” Shaffer said.

One night, as a birthday outing for one of Shaffer’s teammates, the team went to a queer club to celebrate. Inside, Shaffer experienced another world. People wore all types of clothes, kissed each other and performed drag shows.

“I got pulled onstage and I remember shedding a tear because I remember being like, ‘Wow, this is the first time I’ve seen people openly queer,’” Shaffer said. The only other time they saw people like this had been on television shows being made fun of or going to jail. It was true authenticity, uninfringed by what Shaffer was raised to know.

Their freshman-year roommate and best friend, Brittany Cavanaugh from Mount Prospect, also made sure they still had some relatives to rely on. “I had a family party to go to, and I invited

Wes to come with me,” Cavanaugh said. “They were like, ‘Do I have to wear girl clothes?’ And I said no.”

Cavanaugh’s family, much like the basketball team, accepted Shaffer at face value. “I got to know Wes through their heart,” Cavanaugh said. “And when I found out who that person was deep down when they decided to come out as non-binary, it was no surprise to me.”

With a gush of support, Shaffer began exploring life in the city as a nonbinary, gay 18-year-old set on seeing the world. Throughout the rest of their undergraduate experience, the basketball team and Cavanaugh’s family treated Shaffer as their own, inviting them to holiday celebrations and genuinely caring about who they were.

The support also carried them through further education, eventually helping Shaffer pursue coaching, allowing them to establish an LGBTQ center at Indiana University Kokomo, 15 miles from their hometown.

College has become a conduit of national and international exploration to Shaffer, and now that they hold a position at PRISM meant to educate people about the LGBTQ community, they mean to continue pushing Hattiesburg and its people forward.

“Multiple different cultures acknowledge these things as normal,” Shaffer said. “To have bills and policies to take away these civil rights are just rude.” In addition to anti-LGBTQ policy, Shaffer cited the danger of limiting knowledge of other social and cultural backgrounds, such as bans on critical race theory in states such as Florida and Alabama.

Without open conversation and proper policy, according to Shaffer, the stereotypes and pain that they endured during childhood and early college will be perpetuated by anti-LGBTQ action. Regardless, Shaffer said they would repeat every instant of pain from their past to continue fighting for LGBTQ students at USM to have a place. And to them, the future holds promise.

“Individuals are just so resilient here, and they understand that within this day, there’s so much progression,” Shaffer said. “Hattiesburg has a great abundance of it.” According to Shaffer, that guarantees growth, even on the smallest scale, will bloom into much more.

Your donation will support the student journalists of University of Southern Mississipi. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.