In this three-part series, News Editor Caleb McCluskey will uncover Hattiesburg’s past and debate its progress with some of Hattiesburg’s prominent leaders and scholars. In part one, McCluskey asks, “Is Hattiesburg inclusive?”

Hattiesburg is well known as a Civil Rights city and considered to be quite progressive to many of its residents, but to others, there is an undercurrent of racism and prejudice that cannot be overlooked.

“In 2019, we are still dealing with issues of race because I have to raise that issue—because it is one that actually exists,” Ward 2 Councilwoman Deborah Delgado said. “The system of the white majority has not built a progressive community for African Americans.”

Despite Hattiesburg’s movement toward being more inclusive, some believe institutionalized racism is stifling African American voices. While some people believe Hattiesburg is better than it once was, others believe times have changed, but not for the better.

Sixth Avenue, known as the museum district, shines a light on the civil rights movement with Oseola McCarty’s home, the African American Military History Museum and Eureka School Museum, but Forrest County Supervisor Rod Woullard, who represents District 4, said progress does not excuse many issues that persist in Hattiesburg’s culture.

“We cannot legislate morality,” Woullard said. “Until our hearts truly change for one another and toward one another, these problems are going to persist.”

Delgado said her ward has issues with flooding, but she has had trouble fixing the problem. She said she feels if people considered the quality of life of everyone, there would have been a solution to their flooding issue already.

“I think if there were not black and poor people living in those areas, we would have embraced methods for learning how to live with the water many years ago,” Delgado said.

Delgado said Hattiesburg has a large African American population, but because the majority of the black population lives in two wards, they only have a say for two of the five people on the council. According to data released by the American Community Survey published by World Population Review in 2019, African Americans make up a little over 53% of Hattiesburg’s population.

Delgado said redistricting, the process of redrawing electoral districts, has caused the African American voice in the community to be quietened. She said creating another predominantly African American ward could fix the issue.

“If we are the majority, why is it we only control 40% of the votes on the city council,” Delgado said. “The white community controls 60% of the power on the city council, and it’s not right.”

Delgado said she often faces issues of race as a black politician and is sometimes labeled an “angry black woman.”

“When I speak out or speak up, I am an angry black woman,” Delgado said. “If it is one of my white colleagues, that person is active, being aggressive, getting the word out about the community, fighting for the rights of that community, but I am an angry, racist, black woman. No. I want the very same thing that every other community in Hattiesburg has.”

According to Delgado, who has worked as a city councilwoman for 18 years, being an elected official is hard for her because she is always on the defensive and trying to change minds.

“It is difficult to be an elected official and be black in Hattiesburg,” Delgado said. “I find myself in a situation where I am here to get the maximum benefit for my community, but it is hard when I only have the one vote. I am always trying to convince people to vote with me.”

Woullard said there is a large difference between racism and institutionalized racism, which is a system that gives advantages or disadvantages to people based on their race. He said there is not much he can do to change racism, but he has the power to change institutionalized racism.

“If you hate me because of the color of my skin, there ain’t nothing I can do to change that,” Woullard said. “But if it is institutionalized racism, where the system is not there for everybody, and you’re taking my tax dollars and helping to perpetuate that, I have got a say in that.”

Despite the issues Delgado said she sees in Hattiesburg, she still believes it is accepting, but she said there is a catch.

“I think Hattiesburg is pretty accepting because we want to be a place that welcomes people, but I think it is surface level in many instances,” Delgado said. “You can be accepting in terms of what’s counted for the community, but in terms of real participation and real decision making and real engagement, I don’t think so.”

Benjamin Morris is the author of several books, including “Hattiesburg, Mississippi: The History of the Hub City.” He said the answer to “Is Hattiesburg accepting,” depends on whom you ask. He also said factors like being a college and military town make Hattiesburg more accepting than other cities.

“Hattiesburg enjoys three very strong sectors, which traditionally do promote diversity and communication across all lines of society. Not just race,” Morris said.

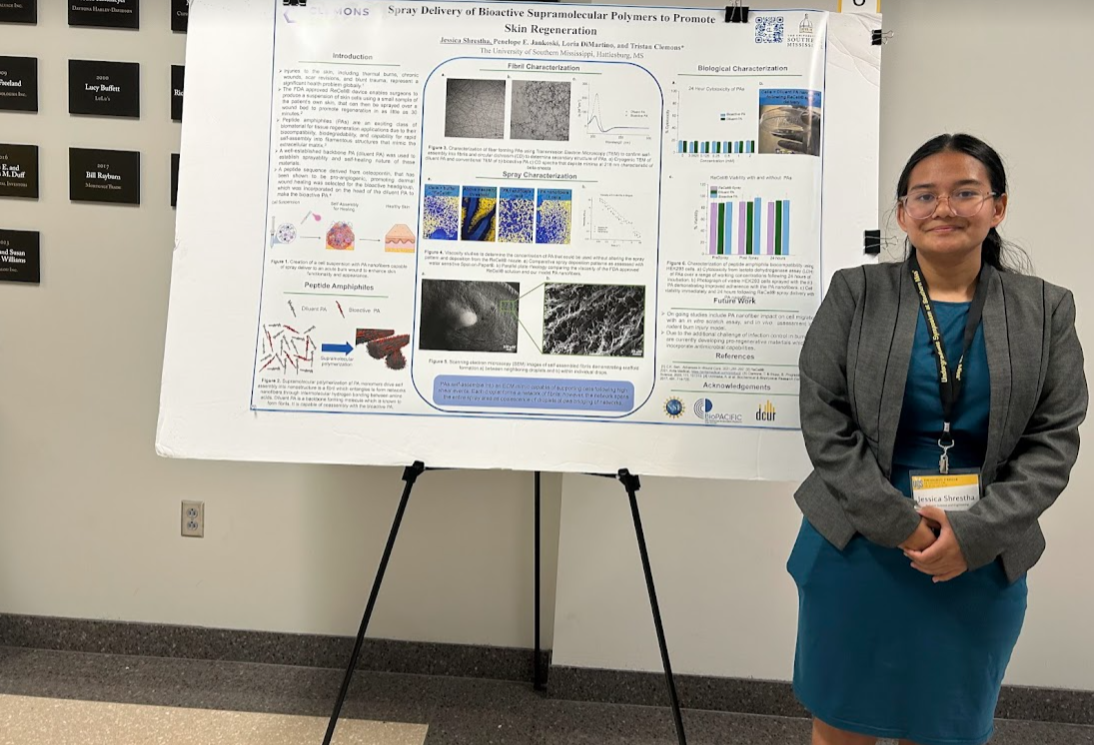

Morris said universities, military service and art assist in building community.

Morris said art societies were a part of Hattiesburg since its founding and art grapples with ideas, stories and experiences beyond one’s own. Because of this, art expands horizons and builds the community as a whole.

“If I am trying to gauge whether a city is inclusive and fun, I always look to see if there is an art scene there. If there’s not, then I get worried,” Morris said. “If there is, then I always feel like I’m on the right track.”

Despite these positive qualities, Morris said there are also some issues he sees in Hattiesburg. Because political positions are often inherited from family and Hattiesburg is a relatively young town, there is less time for opinions to change.

“Frequently, political positions are inherited,” Morris said. “If in Hattiesburg it’s only been a couple generations for the founding to know, I am more likely to expect that some of the political positions that the founders held might not have shifted very much.”

In part two of three, McCluskey will focus on civil rights history in Hattiesburg, prominent figures therein and some of the memorials, markers and memories that are associated with the movement.