Confederate monuments have been a hot topic in recent years, and though Hattiesburg has one itself, it isn’t where true remnants of the Confederacy remain. From the name of Forrest County to the picture of a Klansman hanging in the Forrest County Circuit Court Office, Hattiesburg has its share of fragments of the Confederacy.

The monument is a small piece in the puzzle of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. According to history professor Susannah Ural, Ph.D., who specializes in Civil War history, the Lost Cause was a movement to re-examine how the country viewed the Civil War and the Confederacy. It retold history as a brave and noble fight for state rights rather than a brutal rebellion sparked by slavery.

“Some of the purposes [the United Daughters of the Confederacy] saw for themselves was not only preserving the memory of the Confederacy and what their own fathers had done but also education,” Ural said. “But whose experiences are you trying to preserve?”

Ural said this ideology, which began in earnest in the late 19th century, came up when veterans of the confederacy and their children felt they needed better representation throughout America. Groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the United Sons of the Confederacy began a movement to erect monuments honoring Confederate soldiers.

Councilwoman of Ward 2 Debra Delgado said the Lost Cause is the only instance she knows of where a losing side was able to write the history shown today. She said she understands that people feel they are a part of a great heritage in the South, but they should not forget the ugly side of its history.

“I can appreciate the fact that some people feel that they are a part of a glorious heritage, but their heritage was improperly framed,” Delgado said. “We were never taught the true history of Mississippi, and from what was taught historically about the cases of the Civil War, particularly in the South, it was all wrong. It was about slavery.”

Ural said Confederate monuments are not a monument to the Confederacy but, instead, are monuments to the Lost Cause and should be looked at in that view.

In 1910, The UDC erected a monument in Hattiesburg. Hattiesburg and Forrest County were not established until after the Civil War. Originally, the area was part of Perry County. Ural said history is not black and white, especially in the Pine Belt.

“If you look at that monument, it talks about this united support that was shown in this community during the war,” Ural said. “Perry County and Jones County and the seminary area were incredibly divided in this war.”

Ural said the monument does not cover up the fact that the area was divided, but it does ignore the fact. She said this is the problem with the monument and the Lost Cause ideology because it leads to conflict in memory and people forgetting important events in the history of the area.

“One of the most interesting parts of this area of the Pine Woods and South Mississippi during the Civil War is just how divided this region became,” Ural said.

Ural said South Mississippi was not united in the Civil War. She mentioned Sumrall because the man it is named after was a Civil War veteran that started with the Confederacy but later fought for the Union.

“That was South Mississippi during the Civil War,” Ural said. “It was Unionist, Separationist or split, so to me, that is what monuments like [the one in Downtown] miss.”

Ural said the idea of taking down a monument is not easy either because it has to be agreed upon, voted on, and the cost of removing a monument can add up. She said not only would removal possibly be costly, but there may be no place for the monument to go. She said instead of removing monuments, Mississippi and Hattiesburg should do a better job of teaching the true meaning behind the monuments.

There is also a question of the legality of removing a statue. Ural said it is illegal to remove Confederate statues in Mississippi, but laws like that can be changed. Ural referred to MS code 55-15-81, which specifically prohibits the altercation of any war monument, including the war between the states.

“It’s just a law. Laws can be reviewed. They can be changed,” Ural said.

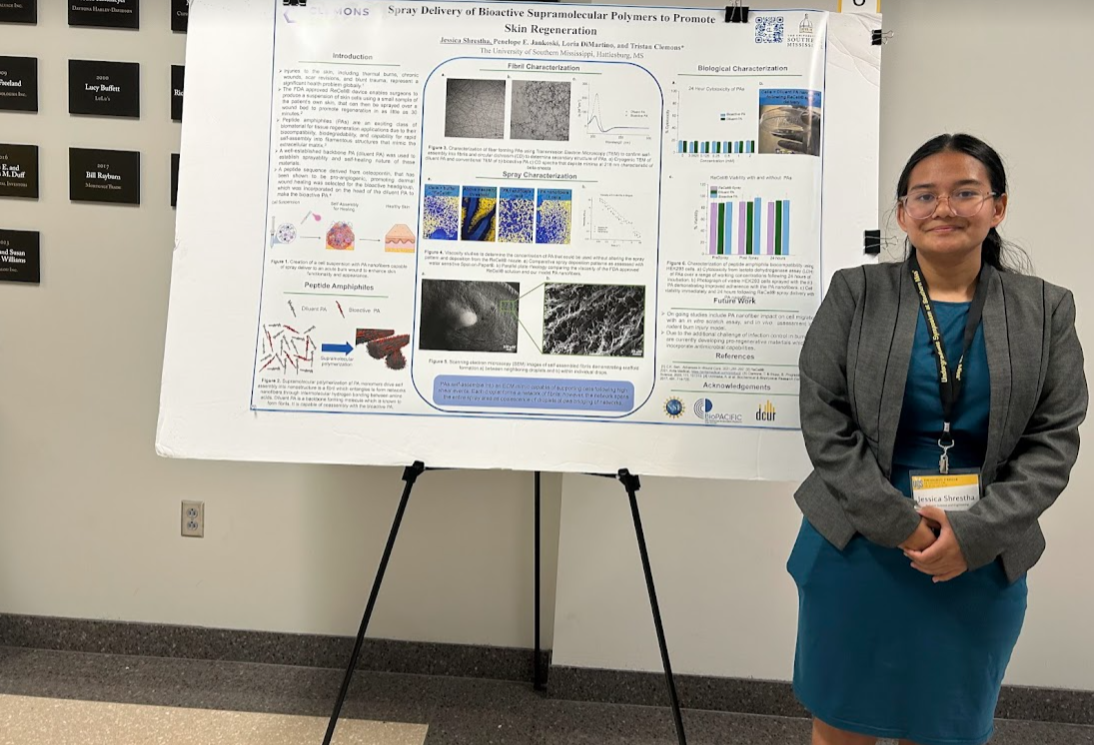

Southern Miss alumna Lisa Foster, who has a Masters of History with a focus on war and society, researched the monument thoroughly. She said a monument is less pressing than the name of Forrest County and the painting of Forest hanging in the Circuit Court Office in Downtown, where the monument is located.

“This bothers me. When you talk about monuments, they’re complex. It’s not really up to me to decide if a monument should stay or go,” Foster said. “There are so many different ways to look at it, but with that painting, there’s not a whole lot of different ways to look at it.”

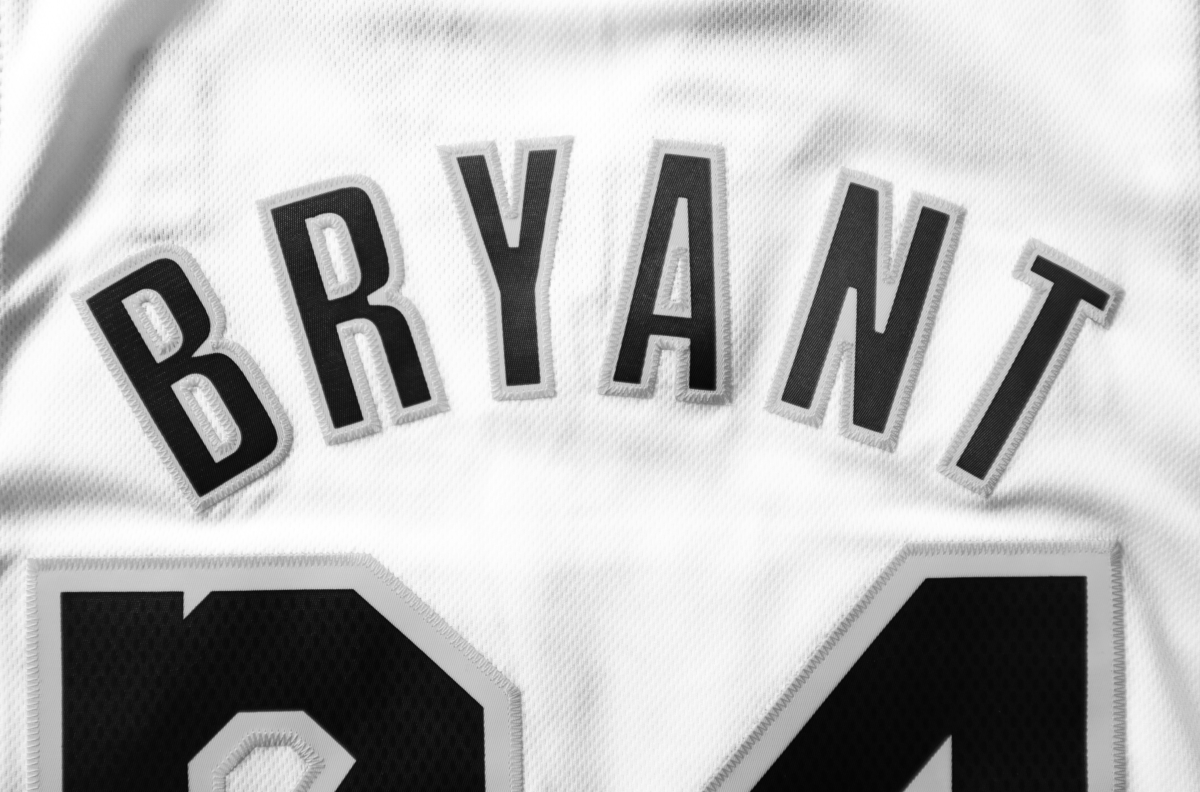

Nathan Bedford Forrest was not only a Confederate general in the Civil War, but he was also an early member of the Ku Klux Klan, a hate group well known for lynching and violence against African Americans, which still exists today. Forrest was not only an early member, but he was the KKK’s first leader, gaining the title of Grand Wizard. According to Ural, there are no records of Forrest ever coming to Perry County or Hattiesburg before the naming of the county or after.

Forrest isn’t just controversial for the role he played in the KKK, but he also is known for the brutal massacre of African American soldiers at Fort Pillow. For these reasons and more, Delgado believes the name of Forrest County should be changed.

“[Forrest County’s name] should be changed,” Delgado said. “My children say we need to cross out the r, but I think it should altogether be changed.”

Delgado said she remembered there being a painting of Forrest in City Hall when she first started working as a councilwoman. She said one day she saw a woman touring some children in City Hall. They stopped at the painting of Forrest. The woman told the children that Forrest County is named after him and went on to say that he was a hero of the Civil War.

“I went straight into the mayor’s office to say, ‘You need to watch what you are allowing in this building because they’re continuing the lie of history to tell these young children,’” Delgado said. “[The painting] disappeared right after that.”

President of the Forrest County Board of Supervisors David Hogan said there must be a vote to change the county’s name. He said he nor the other supervisors could move toward changing the name unless there are significant public concerns.

“As far as the name of the county is concerned, it is my understanding that it is up to the state. I am all for putting [the name change] on the ballot, and if the people of the state are ready to make a change, that is absolutely what we will do.”

Hogan said that he does not want to remove the painting of Forrest nor the Confederate monument because he wants to preserve history—the good and the bad. He said the installment of Vernon Dahmer’s monument and other civil rights memorials in Hattiesburg help to tell a more complete story of the South.

“We want to be inclusive, and I really don’t want to take away from what we are getting ready for Mr. Vernon Dahmer by talking about the Confederate monument,” Hogan said. “I want us to concentrate on Mr. Dahmer.”

Ural said people aren’t learning from Confederate monuments because they are one-sided. She said the addition of Dahmer’s statue is a good example of instead of removing statues, adding statues that tell the history that people want to be remembered.

Forrest County supervisor Rod Woullard, who represents District 4, said he feels the name Forrest should be changed but is more concerned with Forrest’s painting in the Circuit Court office. He said not only is there a painting of Forrest in the hall, but also in their green room, a room meant for a meeting.

Woullard said that one day the painting of Forrest in the green room disappeared, and he was blamed for the disappearance. He said he had not touched the painting though he found it disgraceful to hold a meeting with that painting in the room.

“It was less than 30 days that they had found another picture of him and hung it back up,” Woullard said.

Author’s note: This is the end of the three-part series where News Editor Caleb McCluskey digs into the history of Hattiesburg. He started the process of this series a month ago and has spent hours talking with interviewees, researching historical documents and generally obsessing over the end product. There is a lot more to say about the history of Hattiesburg and its inclusivity, but the only thing left is to understand history and make conclusions based on that. Is Hattiesburg inclusive and accepting? The answer varies from person to person and viewpoint to viewpoint.

Correction: Previously,a sentence said Susannah Ural mentioned the town of Seminary because it was named after a Civil War veteran. Seminary has been changed to Sumrall.